Since its beginning in 2008, DevOps has gone from an underground rebellion by developers to a mainstream movement with representatives in every industry and at every scale. You can see the change just by looking at how people attending DevOps events dress: the black T-shirts are still there, but these days there are lots of suits and ties as well. Another hallmark of this success is companies trying to fit DevOps into their existing conceptual frameworks—hence, the plethora of “ITIL and DevOps” papers out there.

Despite all this success, though, the DevOps movement is still young. Of course, things move fast in IT, but we aren’t talking about a technology or a technique that can be adopted rapidly and spread very widely. Committing to DevOps is a major cultural shift for organizations, and that takes time. Some organizations have been doing DevOps for five years and have fully re-engineered their processes around this new approach, but most are still only at the beginning of their DevOps journey. As William Gibson said, “The future is here; it’s just not evenly distributed.”

First Things First: Speed Up Releases

The early phase of DevOps adoption focuses on activities around releasing code to production, because that was the bottleneck that the DevOps movement was originally created to break. While it still may be too soon to declare victory, it’s safe to say the improvement in the release process is enormous. Today, any new project that does not propose to implement DevOps principles would have to have a very good reason and explanation.

Notice that qualification about new projects. It’s easy to adopt DevOps methodologies and expectations in a greenfield situation; however, it is much harder in a brownfield project, where previous cultural norms have been expressed in tooling and processes that are hard to change in-flight. The good thing is that over time, the old way of doing things will die off naturally, as code bases get re-engineered, ported and replaced. Eventually, every project will be a DevOps project.

Are We Running So Fast That Others Can’t Keep Up?

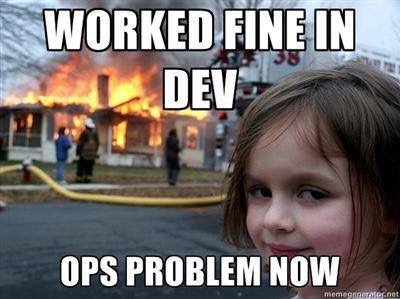

DevOps, however, is not just about release and deployment. It also covers operation of what has been deployed. It’s right there in the name, after all! Coming from an operations background, though, there can be a feeling that DevOps is not for “people like me.” Some simplistic interpretations of DevOps focus on the sometimes adversarial relationship between Dev and Ops, forgetting that good Ops people are just as incentivized as Devs to get Devs more involved in Ops.

One of the difficulties that arise when engineers try to “do the DevOps” without involving Ops is that Ops are not ready to join in. When Dev are doing non-agile releases on an 18-month cycle, Ops have a certain set of assumptions about what a release represents for them. Doing these sorts of monolithic releases is a major pain for Ops for a while, but there will be plenty of time to get ready for it, and other required activities can be scheduled around that release.

One of those important dependencies is preparing the monitoring and management of the code that is being deployed. What needs to be instrumented, where do those feeds need to go, what needs to be in place to make sense of those feeds when they arrive, who needs to jump when one of the feeds goes red, and so on. There is a lot going on in the NOC that Devs are not always aware of.

If Devs suddenly show up with a more Agile cadence of a release every couple of weeks, Ops are simply not going to be able to adapt their existing tools and process on the fly to that new cadence. When you have months of lead time, it’s feasible to write and modify extensive sets of rules and filters to make sense of monitoring data, filter out the cruft, and route the remainder correctly. When your lead time on a release is measured in days or hours—not so much.

Devs should remember that “infrastructure as code” also includes debugging that code. Adopting release automation, containerization or whatever will be the next cool tool will not solve the problem on its own. Bridget Kromhout has a wonderful articulation of this mechanism:

Containers will not fix your broken culture. Microservices won’t prevent your two-pizza teams from needing to have conversations with one another over that pizza. No amount of industrial-strength job scheduling makes your organization immune to Conway’s Law, which states that “organizations which design systems … are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.

Leaving aside the communications barriers that all too often still exist between Dev and Ops, one of the constraints that Ops teams have to deal with is that Ops is segmented into many different teams, each of which deals only with one area or one technology. These days, though, problems tend to have symptoms that cross these domain boundaries, and so operations teams have to communicate with each other.

The historical ways of doing this are not very efficient, relying on ticket ping-pong, escalations, war-rooms and good old blame-storming. What do you think happens if you suddenly accelerate a system like that? The answer is that it just torques itself into scrap.

Completing the DevOps Culture Shift

The good news is that others have been where you are now, and there are both tools and techniques that can help you operate what you have developed. In common with the rest of the DevOps movement, it’s as much a cultural shift as a technological one. Ops teams need to start thinking of operations in a new way.

One aspect of that change is the ongoing shift to immutable architecture, also known as puppies vs. cattle. Another is to enable efficient communication across support domains. Today, like in the parable of the blind men and the elephant, support teams often get hold of different bits of the problem, misidentifying them because they only have partial information, and therefore cannot truly resolve the problem. Nobody really has a complete view of the whole elephant, except perhaps for some savant who can be reached only after many escalations—and really has better things he or she should be doing.

If Ops teams can work side by side with Dev, on the other hand, there is a virtuous cycle that becomes possible, with efficient operations removing even more friction from the development process. Communications are the key, whether that means machine-to-machine feeds, human-to-human conversation or machine-to-human interaction. Organizations that get this right reap enormous rewards in both Dev and Ops.

Dominic Wellington serves as Moogsoft’s Chief Evangelist