In designing and organizing a two-day workshop on microservices, I’ve been thinking a lot about how to explain monolith application decomposition and what a transition to microservices might look like. This is a small subset of that material, but I wanted to share it to get feedback (in the workshop we go into more detail about whether you should even break up your monolith). This is based on my own tried-and-true real-life experience, as well as my work with the many Red Hat customers I’ve met in North America over the last few years. Part I explores the architecture, while the second part (to be released shortly) will cover some technology that can greatly help in this area.

Before we dig in, let’s set up some assumptions:

- Microservices architecture is not appropriate all the time (to be discussed in length)

- If we find we should go to a microservices architecture, we have to decide what happens with the monolith

- In rare cases, we’ll want to break out parts of the monolith as is; in most other cases we’ll want to either build new features or re-implement existing business processes around the monolith (in a strangler fashion)

- In the cases where we need to break out functionality or re-implement, we cannot ignore the fact that the monolith is currently in production taking load and probably bringing lots of business value

- We need a way to attack this problem with very little disruption to the overall business value of the system

- Since the monolith is the monolith, it will be very difficult/nearly impossible to make changes to the data model/database underneath it

- The approach we take should reduce the risk of the evolution and may take multiple deployments and releases to make it all happen

Extracting Microservices

If you dig into the conference/blog posts this topic, often times you’ll find it offers these words of advice:

- Organize around nouns

- Do one thing and one thing well

- Single responsibility principle

- It’s hard

I’m afraid this advice is quite useless.

The more useful material discusses an approach that at times look something like this:

- Identify modules (either existing or new ones to write)

- Break out tables that correspond to those modules and wrap with a service

- Update the code that once relied on the DB tables directly to call this new service

- Rinse and repeat

Let’s take a closer look:

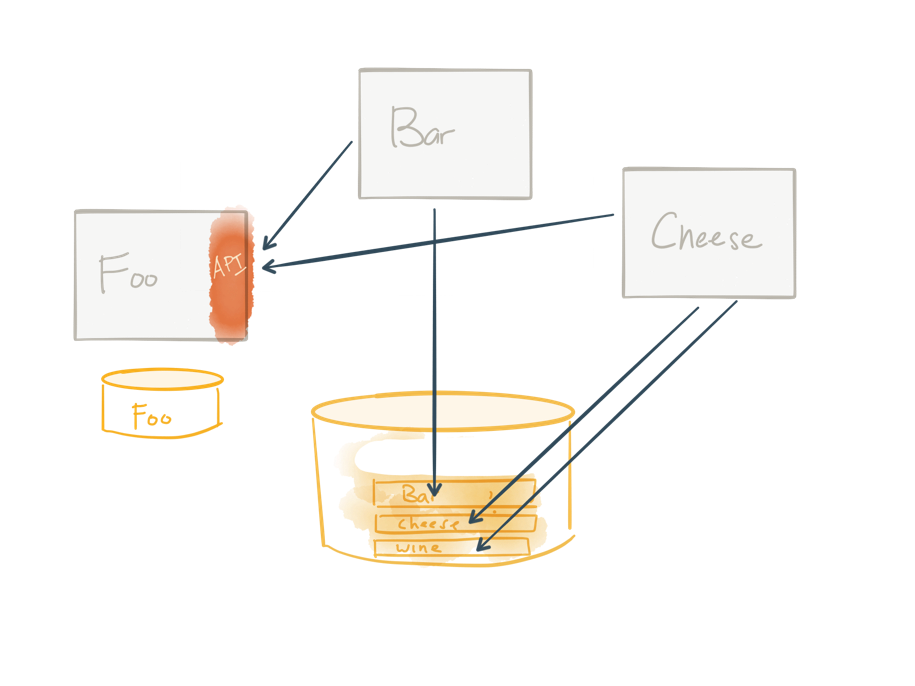

Step 1: Identify modules

You start off with some nasty monolith. In the image above I’ve simplified this to denote the different modules and database tables that may be involved here. We identify which modules we wish to break out of the monolith and figure out which tables are involved and then go from there. Of course, the reality is monoliths are far more entangled with modules conflated with each other (if any modules). More on that in a bit.

Step 2: Break out database tables, wrap with service, update dependencies

The next step is to identify which tables are used by the Foo module and break those out into its own service. This service is now the only thing that can access those Foo tables. No more sharing tables! This is a good thing. And anything that once did refer to Foo must now go through the API of the newly created service. In the above image, we update the Bar and Cheese service to now refer to Foo service whenever it needs Foo things.

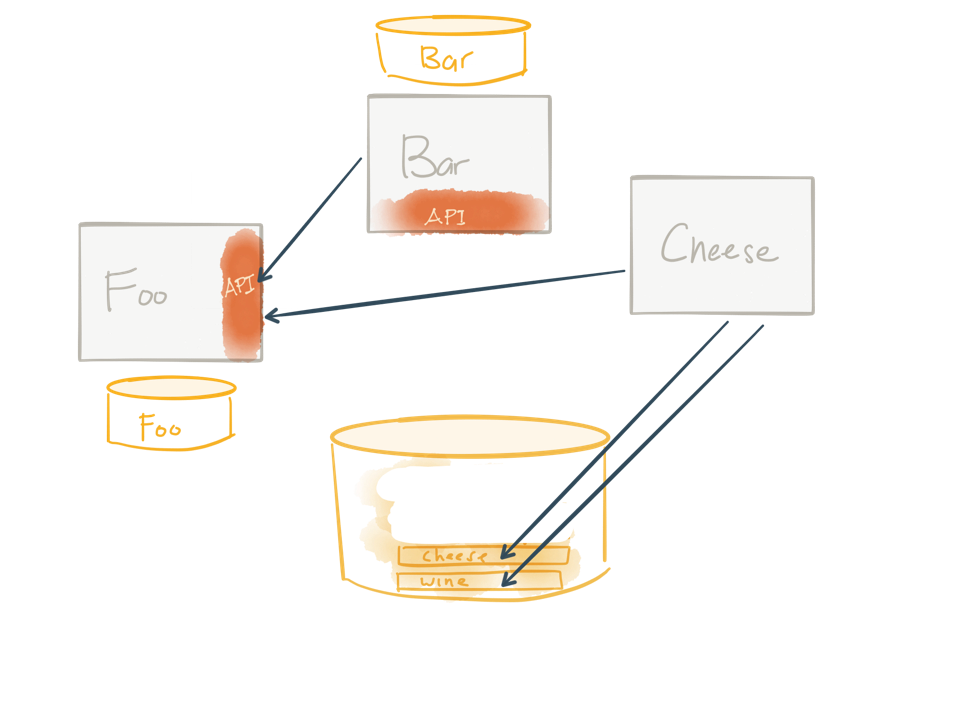

Step 3: Rinse and repeat

The last step is to repeat this effort until you’re left with no more monolith. In the above image, we’ve done the same thing for the Bar service and you can see that we’re moving to an architecture in which services own their data and expose APIs—which sounds similar to what we hear about microservices.

While this approach is generally a decent set of guidelines, it misses a lot of the fidelity that we really need when going down this path. For example, this approach glosses over the fact that we cannot just stop the world to remove tables from databases. Also:

- Rarely do monoliths lend themselves to nice and neat modularization

- The relationships between tables can be highly normalized and exhibit tight coupling/integrity constraints among entities

- We may not fully understand what code in the monolith uses which tables

- Just because we’ve extracted tables to a new service doesn’t mean the existing business processes stop so we can migrate everyone to use the service

- There will be some ugly migration steps that cannot be wished away

- There is probably a point of diminishing returns where it doesn’t make sense to break things out of the monolith

– Etc., etc.

Let’s take a look at a concrete example and what the approach/pattern would look like and the options we may have as we go.

Concrete example

This example comes from the aforementioned workshop. I’ll be adding some color around the splitting of the services, but there are more detailed guidelines around Domain Driven Design, coupling models and physical/logical architecture that we go into for the workshop that we’ll leave out for now. On the surface, this approach appears to deal with decomposition of existing monolith functionality but applies equally well to adding new functionality around the monolith; this may be the more likely case, since making changes to the monolith can be quite risky.

Meet the monolith

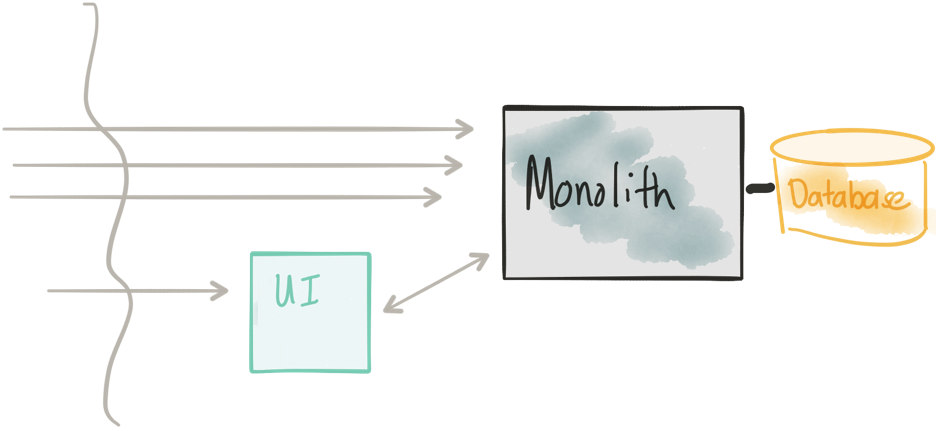

This is the Monolith that we’ll be exploring. It’s based on the TicketMonster tutorial from developers.redhat.com. That tutorial explores building a typical Java EE application and ends up being a good example—it’s not overly complicated but has enough meat to it we can use it to illustrate key points. In part two of this blog post we’ll actually go deeper into the technology frameworks/platforms.

This is the Monolith that we’ll be exploring. It’s based on the TicketMonster tutorial from developers.redhat.com. That tutorial explores building a typical Java EE application and ends up being a good example—it’s not overly complicated but has enough meat to it we can use it to illustrate key points. In part two of this blog post we’ll actually go deeper into the technology frameworks/platforms.

From this image, we’re illustrating that the Monolith has all modules/components/UI co-deployed talking to a single monolithic database. Whenever we need to make a change, we need to deploy all of it. Imagine the application is 10+ years old and very difficult to change (for all the technical reasons, but also for team/organization structure reasons). We would like to break out the UI and key services that will allow the business to make changes faster and independently from each other to experiment with delivering new customer and/or business value.

Considerations

- Monolith (code and database schema) is hard to change.

- Changes require complete re-deployment and high coordination between teams.

- We need to have lots of tests in place to catch regressions.

- We need a fully automated way to deploy.

Extract the UI

In this step, we’re going to decouple the UI from the Monolith. Actually in this architecture, we don’t actually remove anything from the Monolith. We start to reduce risk just by adding a new deployment that contains the UI. The new UI component in this architecture should be very close (exactly?) to the same UI that’s in the Monolith and just calls back to the Monolith’s REST API. Of course, this implies the monolith has a reasonable API that an external UI could use. We may find this is not the case; typically, this type of API may resemble more of an “internal” API, at which point we’d need to think about some integration between the separate UI component and the backend monolith and what a more consumable public-facing API might look like.

We can deploy this new UI component into our architecture and use our platform to slowly route traffic to it while still routing to the old monolith—this way we can introduce it without taking downtime. Again, in the second part of the blog post we’ll look at this in more detail; however, the concept of dark launch/canary release/rolling release are all very important here (and for subsequent steps).

Considerations

- Don’t modify the monolith for this first step; just copy/past UI into separate component.

- We need to have a reasonable remoting API between the UI and monolith—this may not always be the case.

- Security surface increases.

- We need a way to route/split traffic in a controlled manner to the new UI and/or the monolith directly to support dark launch/canary/rolling release.

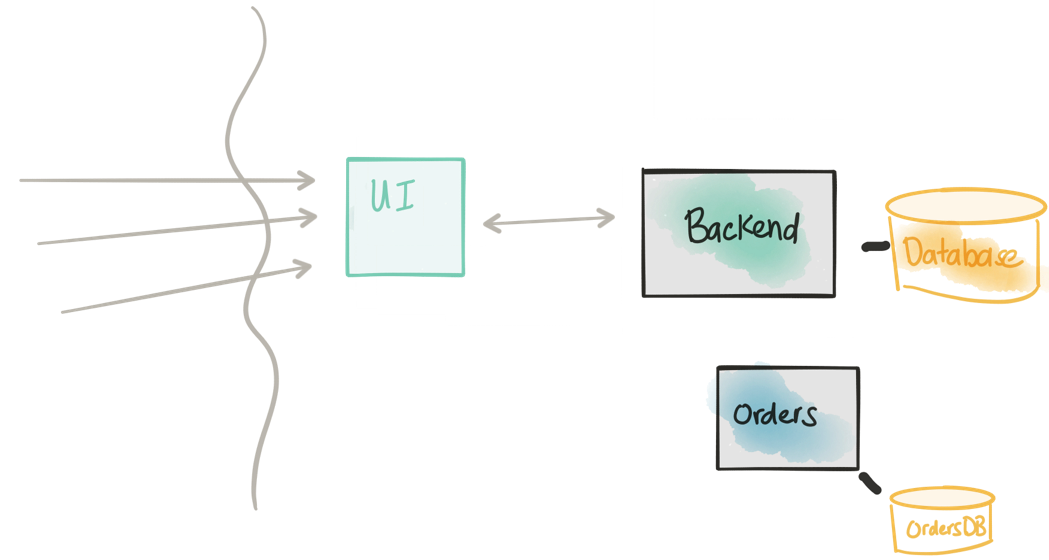

Drop the UI from the monolith

In the previous step, we introduced a UI and slowly rolled over traffic to the new UI (which communicated directly with the Monolith). In this step we do a similar deployment strategy, except now we slowly release a new deployment of the monolith with the UI removed. We can bleed traffic over and stop/rollback if we see issues. Once we have all traffic going to our Monolith without the UI (termed Backend from here on) we can remove the Monolith deployment completely. By separating out the UI, we’ve now made a small decomposition to our monolith and reduced our risk by relying on dark launches/canaries/rolling releases.

In the previous step, we introduced a UI and slowly rolled over traffic to the new UI (which communicated directly with the Monolith). In this step we do a similar deployment strategy, except now we slowly release a new deployment of the monolith with the UI removed. We can bleed traffic over and stop/rollback if we see issues. Once we have all traffic going to our Monolith without the UI (termed Backend from here on) we can remove the Monolith deployment completely. By separating out the UI, we’ve now made a small decomposition to our monolith and reduced our risk by relying on dark launches/canaries/rolling releases.

Considerations

- We are removing the UI component from the monolith.

- This requires (hopefully) minimal changes to the monolith (deprecating/removing/disabling the UI).

- Again, we use a controlled routing/shaping approach to introduce this change without downtime.

Introduce a new service

In the next step, and skipping the detail of coupling, Domain Driven Design, etc., we’re introducing a new service: the Orders service. This is a critical service that the business wants to change more frequently than the rest of the application and has a fairly complicated write model. We may also explore architectural patterns such as CQRS with this model, but I digress.

We want to focus on the boundary and API of the Orders service in terms of the existing implementation in the Backend. In reality, this implementation is more likely to be a rewrite than a port of existing code, but the idea/approach here is the same either way. Notice in this architecture, the Orders service has its own database. This is good; we’re shooting for a complete decoupling. However, we’re not there yet. There are a few more steps we need to consider/undertake.

This step would also be a good time to consider how this service plays in the overall service architecture by focusing on the Events it may emit or consume. Now is a great time to perform an activity such as Event Storming and think through the events we should publish as we start to take transactional workloads. These events will come in handy when we try to integrate with other systems and even as we evolve the monolith.

- We want to focus on the API design/boundary of our extracted service.

- This may be a rewrite from what exists in the monolith.

- Once we have the API decided, we will implement a simple scaffolding/place holder for the service.

- The new Orders service will have its own database.

- The new Orders service will not be taking any kind of traffic at this point.

Connect the API with an implementation

At this point, we should be continuing to evolve the service’s API and domain model and how it’s implemented in code. This service will store any new transactional workloads into its own database and keep it separate from any other services. Any services needing access to this data would have to go through an API.

At this point, we should be continuing to evolve the service’s API and domain model and how it’s implemented in code. This service will store any new transactional workloads into its own database and keep it separate from any other services. Any services needing access to this data would have to go through an API.

One thing we will not be able to ignore: Our new service and its data is intimately related (if not exactly the same in some areas) to the data in the monolith. This is highly inconvenient, actually: As we start to build the new service, we’ll need existing data from the Backend service’s database. This could get really tricky because of the normalization/FK constraints/relationships in the data model. Reusing an existing API on the monolith/backend may be too coarse-grained and we’d have to reinvent a lot of gymnastics to get the data in the shape we want.

What we want to do is get access to the data from the Backend in read-only mode through a lower-level API and have a way to shape the data/data model into the model that fits better with the domain model in our new service. In this architecture, we’re going to temporarily connect to the Backend database directly and query the data directly as we need. For this step, we need a consistency model that reflects a direct database access.

Some of you may cringe initially at this approach. And you should. However, the plain fact is this approach is totally valid and has been used successfully in highly critical systems—and more importantly, is not the end-state architecture (if you think this may end up being end-state architecture, stop and do not do this). You also may point out that connecting up to the Backend database, querying data and massaging it into the right shape we need for our new service’s domain model involves a lot of nasty integration/boilerplate. I’d argue that since this is temporary in our evolution of the monolith, it’s probably OK: ie, use technical debt to your advantage and then quickly pay it down. However, there is a better way. I’ll discuss this in part 2 of this blog post.

Alternatively, some of you might be saying, “Well, just stand up a REST API in front of the Backend database that gives lower-level data access and have the new service call that.” This is also a viable approach, but not without its own drawbacks. Again, will discuss this in more detail in part 2.

Considerations

- The extracted/new service has a data model that has tight coupling with the monolith’s data model by definition.

- The monolith most likely does not provide an API at the right level to get this data.

- Shaping the data even if we do get it requires lots of boilerplate code.

- We can connect directly to the backend database temporarily for read-only queries.

- The monolith rarely (if ever) changes its database.

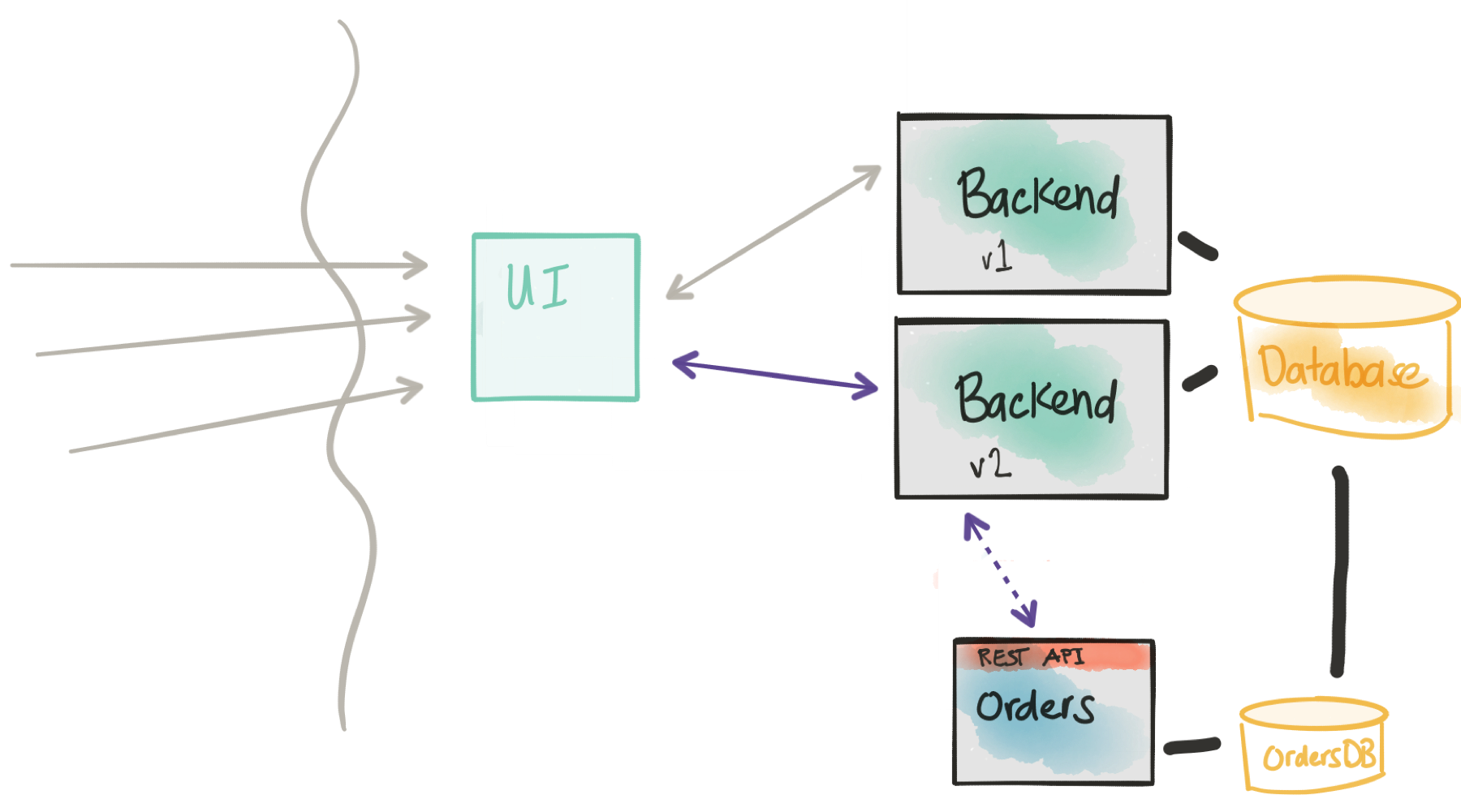

Start sending shadow traffic to the new service (dark launch)

In our next step of this approach/pattern, we need a way to actually direct traffic to our new service. However, we don’t want to do a big-bang release. We don’t want to just throw this into our production traffic (especially considering that this example uses an “order” service that takes orders! We don’t want to introduce any issues with taking orders!). Although we cannot easily change the underlying monolith database, if there’s hope, you may be able to make changes to the monolith application carefully to call our new orders service. I highly recommend Michael Feather’s “Working Effectively with Legacy Code” if you’re unsure of how best to do this. There are patterns such as the Sprout Method/Class and/or Wrap Method/Class that could help.

In our next step of this approach/pattern, we need a way to actually direct traffic to our new service. However, we don’t want to do a big-bang release. We don’t want to just throw this into our production traffic (especially considering that this example uses an “order” service that takes orders! We don’t want to introduce any issues with taking orders!). Although we cannot easily change the underlying monolith database, if there’s hope, you may be able to make changes to the monolith application carefully to call our new orders service. I highly recommend Michael Feather’s “Working Effectively with Legacy Code” if you’re unsure of how best to do this. There are patterns such as the Sprout Method/Class and/or Wrap Method/Class that could help.

When we make a change to our monolith/backend, we don’t want to replace the old code path. We want to put in just enough code to allow both the old or the new code path to run—potentially even in parallel—as deemed fit. Ideally, the new version of the monolith with this change will allow us to, at run time, control whether we’re sending to the new Orders service, the old monolith code path or both. In any combination of call paths, we want to instrument heavily to understand any potential deviations between the old and new execution path.

Another thing to note: If we enable the monolith to send the execution to the old code path as well as calling our new service, we need a way to flag this transaction/call to the new service as a “synthetic” call. If your new service is less critical than in this example, an order service, and you can deal with duplicates, then maybe this synthetic-request identification is less important. If your new service tends to serve more read-only traffic, again, you may not worry as much about identifying synthetic transactions. In the case of a synthentic transaction, however, you want to be able to run the entire service end to end including storing into the database. You may take options here to either store the data with a “synthetic” flag or just roll back the transaction if your data store supports that.

The last thing to note here is when we make our change to the monolith/backend, we again want to use a dark launch/canary/rolling release approach. We will need our infrastructure to support this. We will look closer at this in the second part.

The last thing to note here is when we make our change to the monolith/backend, we again want to use a dark launch/canary/rolling release approach. We will need our infrastructure to support this. We will look closer at this in the second part.

At this point, we’re forcing the traffic back through the monolith. We’re trying not to perturb the main call flow as much as possible so we can quickly roll back in the event a canary doesn’t go well. On the other hand, it may be useful to deploy a gateway/control component that can more finely control the call to the new service instead of forcing to the monolith. In this case, the gateway would have the control logic whether to send the transaction to the monolith, to the new service or both.

Considerations

- Introducing the new Orders service into the code path introduces risk.

- We need to send traffic to the new service in a controlled manner.

- We want to be able to direct traffic to the new service as well as the old code path.

- We need to instrument and monitor the impact of the new service.

- We need ways to flag transactions as “synthetic” so we don’t end up in nasty business consistency problems.

- We wish to deploy this new functionality to certain cohorts/groups/users.

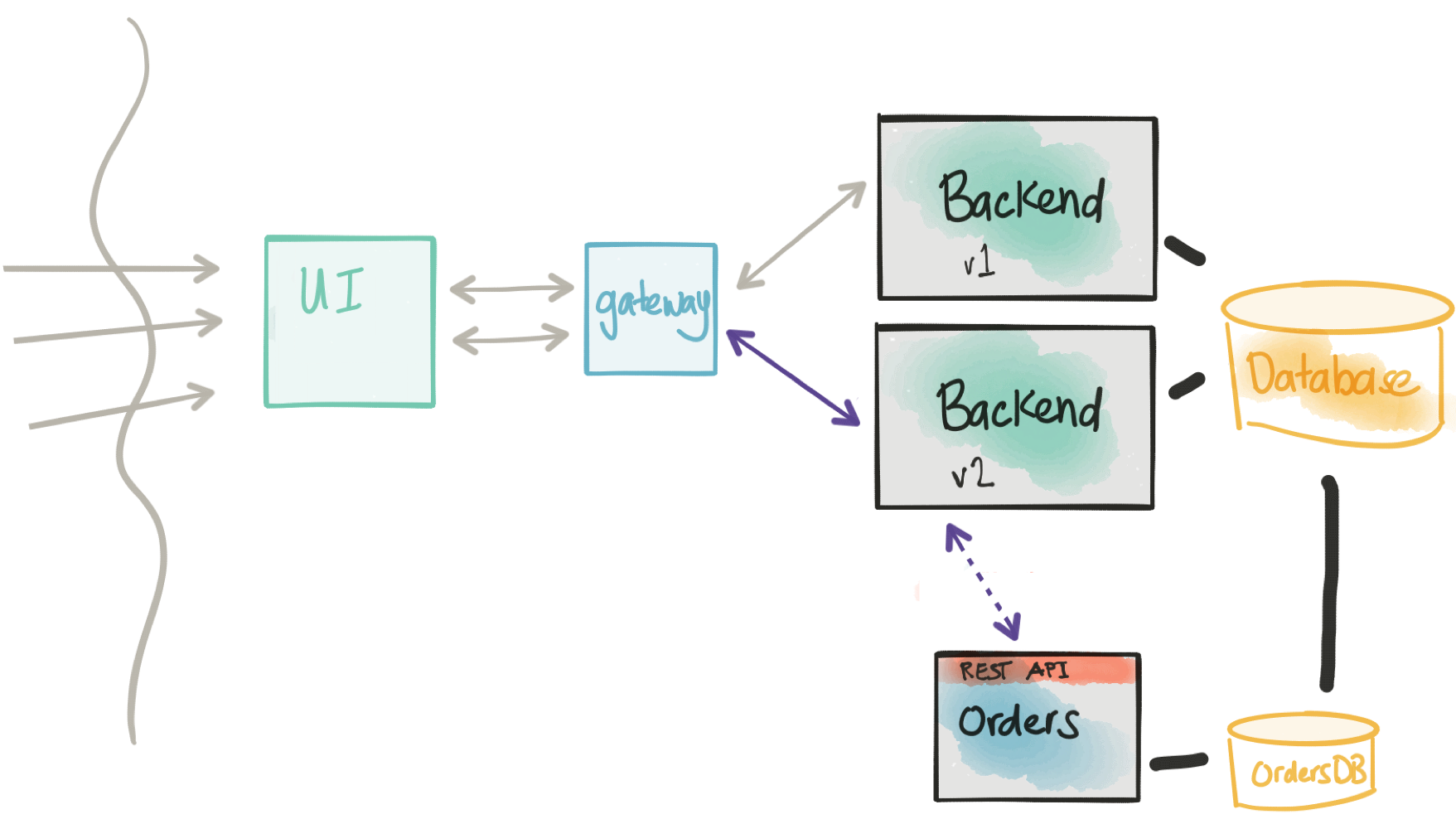

Canary/Rolling Release to new service

If we find the previous step does not introduce negative impacts to our transaction path and we have high confidence through our testing and initial experimentation in production with shadowing the traffic, we can configure the monolith to actually send traffic over to the new service. In this case, we need to be able to specify certain cohorts/groups/users to always go to the new service and we’re slowly draining the real production traffic that goes through the old code path. We can increase the rolling release of our Backend service until all of our users are on the new Orders microservice.

If we find the previous step does not introduce negative impacts to our transaction path and we have high confidence through our testing and initial experimentation in production with shadowing the traffic, we can configure the monolith to actually send traffic over to the new service. In this case, we need to be able to specify certain cohorts/groups/users to always go to the new service and we’re slowly draining the real production traffic that goes through the old code path. We can increase the rolling release of our Backend service until all of our users are on the new Orders microservice.

One point of risk we need to make concrete: Once we start rolling live traffic (non-shadow/synthetic traffic) over to the new service, we’re expecting users that match the cohort group to go to this new service always. We’re not able to switch back and forth between old and new code paths. In this case, if we do need to rollback, this will involve more coordination to move any new transactions from the new service back to a state that the old monolith could use. Hopefully this doesn’t happen, but is something to note and plan for (and test!).

Considerations

- We can identify cohort groups and send live transaction traffic to our new microservice.

- We still need the direct database connection to the monolith because there will be a period of time where transactions will still be going to both code paths.

- Once we’ve moved all traffic over to our microservice, we should be in position to retire the old functionality.

- Note that once we’re sending live traffic over to the new service, we have to consider the fact a rollback to the old code path will involve some difficulty and coordination.

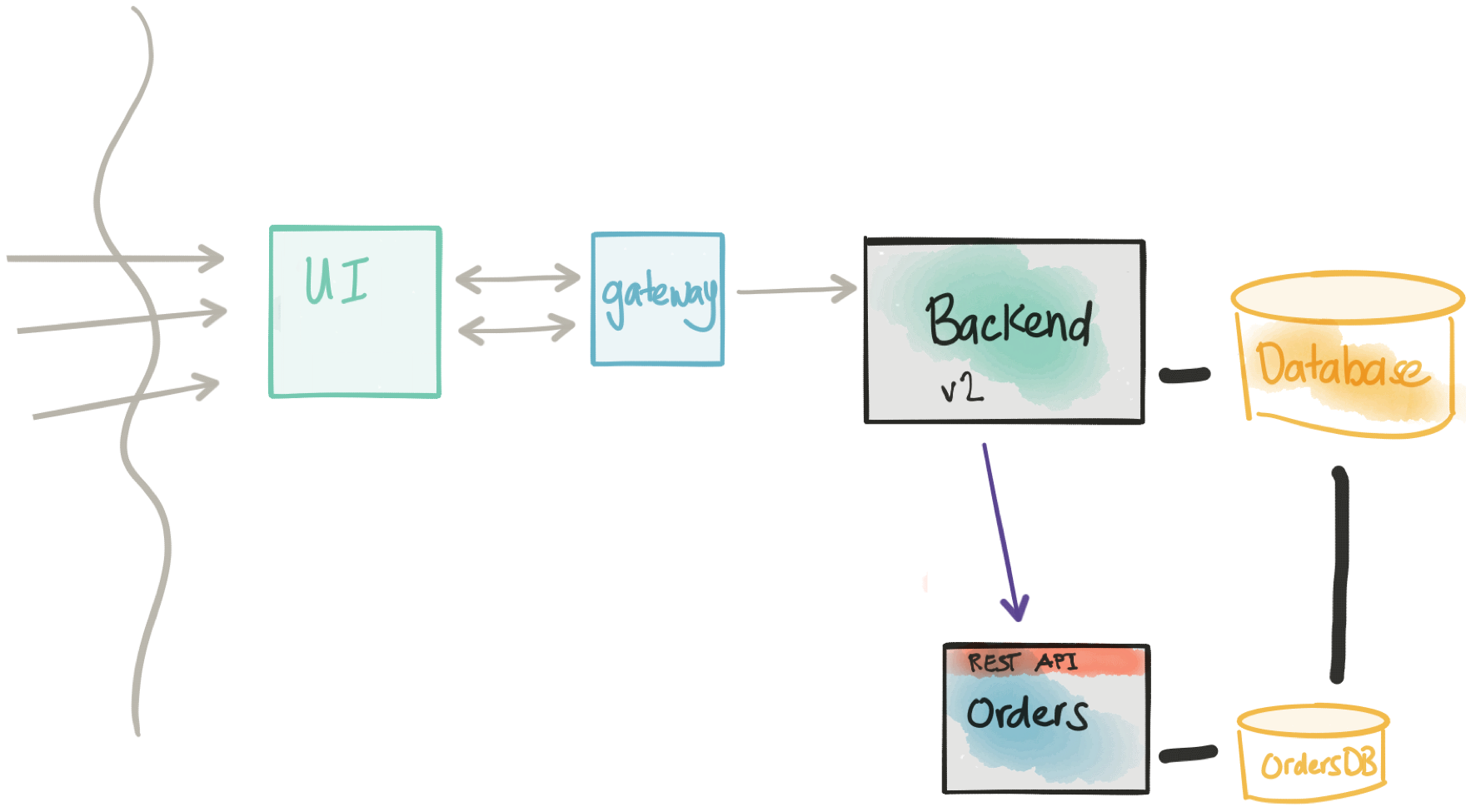

Offline data ETL/migration

At this point, we should have our Orders microservice taking live production traffic. The Monolith or Backend is still around handling other concerns, but we have successfully migrated service functionality out of the monolith. Our immediate pressing concern now is to pay off the technical debt we’ve borrowed when we created a direct database connection between our new microservice and the Backend service. Most likely this would involve some kind of one-time ETL from the monolith database to the new service. The monolith may be required to still keep that data around in a read-only mode (think: regulatory compliance, etc.). If this is shared reference data (ie, read only) this should be okay. We must make sure that the data in the monolith and the data in the new microservice is not some shared/mutable data. If the data is shared/mutable, then we can end up in divergent data/data ownership problems.

At this point, we should have our Orders microservice taking live production traffic. The Monolith or Backend is still around handling other concerns, but we have successfully migrated service functionality out of the monolith. Our immediate pressing concern now is to pay off the technical debt we’ve borrowed when we created a direct database connection between our new microservice and the Backend service. Most likely this would involve some kind of one-time ETL from the monolith database to the new service. The monolith may be required to still keep that data around in a read-only mode (think: regulatory compliance, etc.). If this is shared reference data (ie, read only) this should be okay. We must make sure that the data in the monolith and the data in the new microservice is not some shared/mutable data. If the data is shared/mutable, then we can end up in divergent data/data ownership problems.

Considerations

- Our new Orders microservice is now in the last throes of becoming fully autonomous.

- We need to pay down the technical debt we borrowed when we connected the Orders service database to the Backend

- We will have a one-time ETL for the data that should reside in the Orders

- We need to be mindful of divergent data problems.

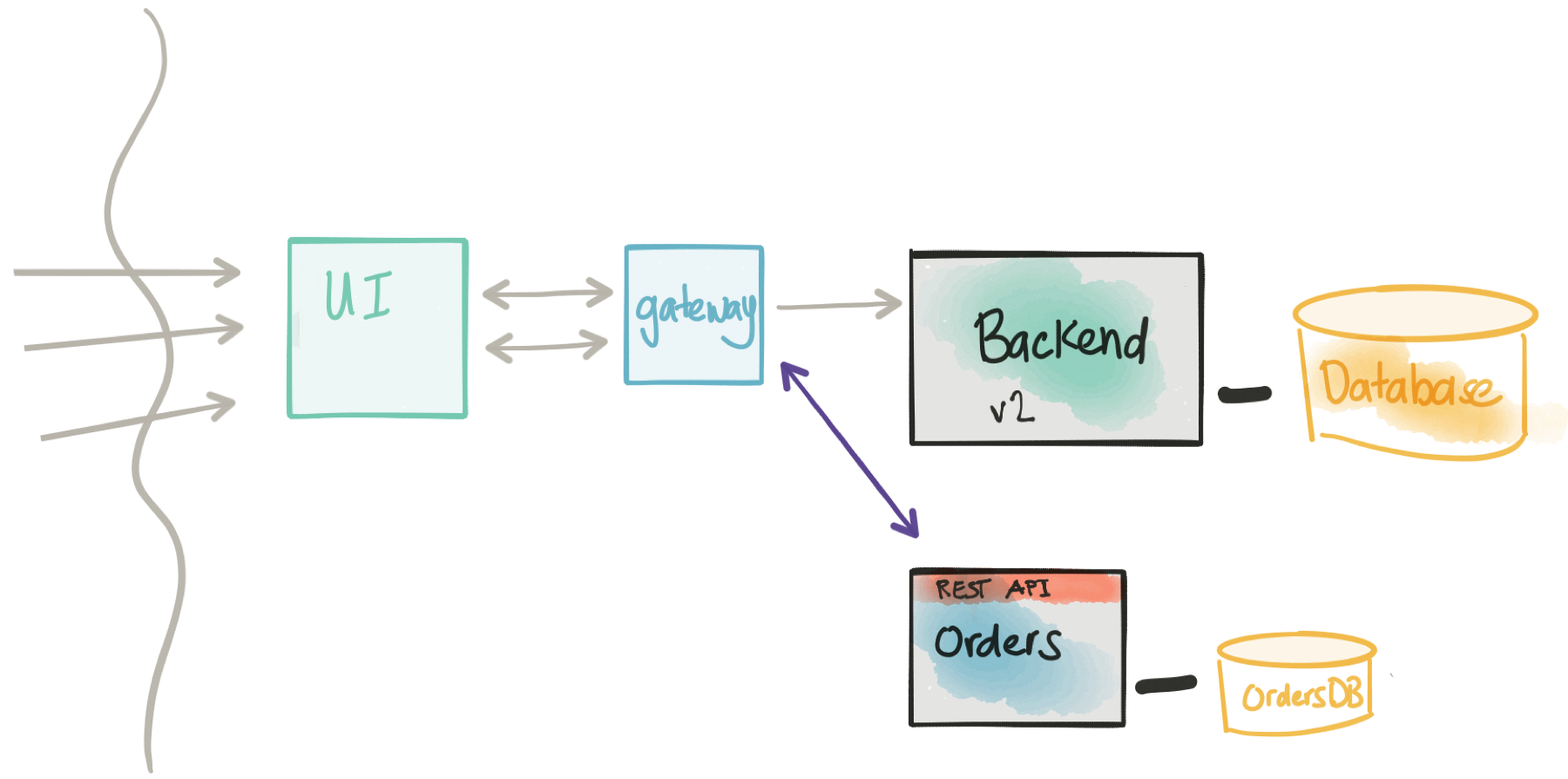

Disconnect/decouple the datastores

Once we’ve completed the previous step, we should have our new Orders microservice-independent and ready to participate in a services architecture. The steps presented here all have their own considerations, pros and cons. We should aim to satisfy all of the steps and not leave technical debt to accrue interest. Of course, there will be variations on this pattern, but the approach is sound.

Once we’ve completed the previous step, we should have our new Orders microservice-independent and ready to participate in a services architecture. The steps presented here all have their own considerations, pros and cons. We should aim to satisfy all of the steps and not leave technical debt to accrue interest. Of course, there will be variations on this pattern, but the approach is sound.

In the next blog post, I’ll show how to do these steps with the example service I’ve referred to previously and dig deeper into some of the tools, frameworks and infrastructure that helps assist. We’ll look at things such as Kubernetes, Istio, feature-flag frameworks, data-view tools, and test frameworks.

Part 2 will follow in December

Follow along (@christianposta) on twitter or http://blog.christianposta.com for the latest updates and discussion.