The past 15 years have been rough on software testers. The rise and fall of outsourcing, Agile growing from a manifesto to a movement and ever-shrinking release cycles have all taken a toll. By 2011, Albert Savoia walked on stage at the Google Test Automation Conference (GTAC) dressed as the Grim Reaper and declared testing dead. Since then, the emphasis on the “automation” part of “test automation” has fueled demand for Software Development Engineers in Test (SDETs) and left many testers wondering if they must learn programming to save their jobs.

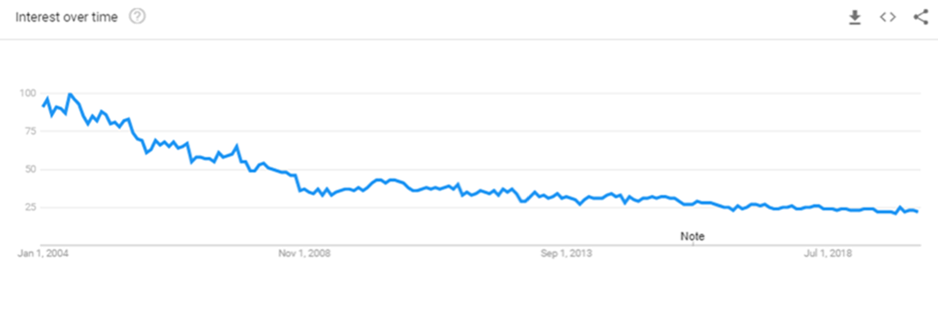

If you look at how frequently people are searching for “software testing” on Google, the trends seem to suggest that the profession is, if not dead, at least flatlining.

However, I think the times are a-changin’. The pendulum will be swinging back—to the point where software testing could be the comeback kid of the 2020s. Sounds crazy, I know. But consider some developments that could turn things around.

However, I think the times are a-changin’. The pendulum will be swinging back—to the point where software testing could be the comeback kid of the 2020s. Sounds crazy, I know. But consider some developments that could turn things around.

Developers Don’t Want to Bear the Testing Burden

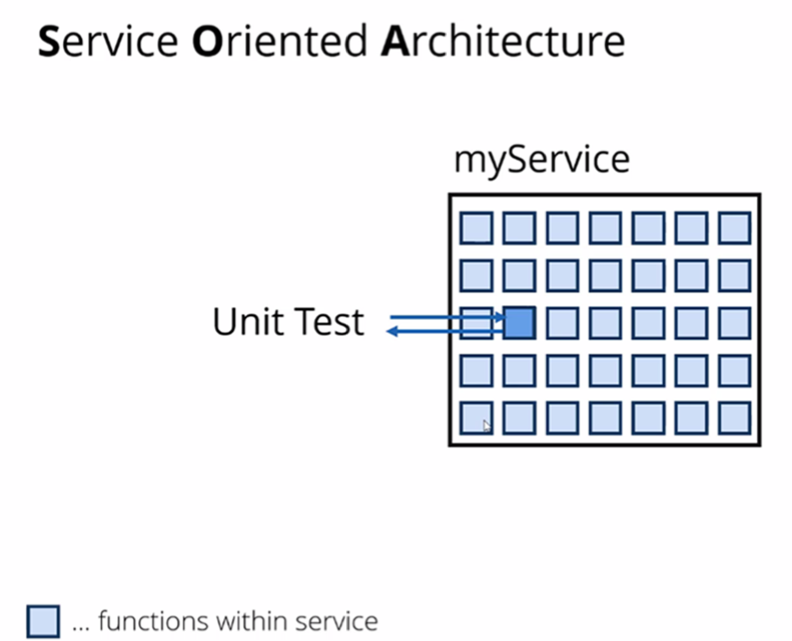

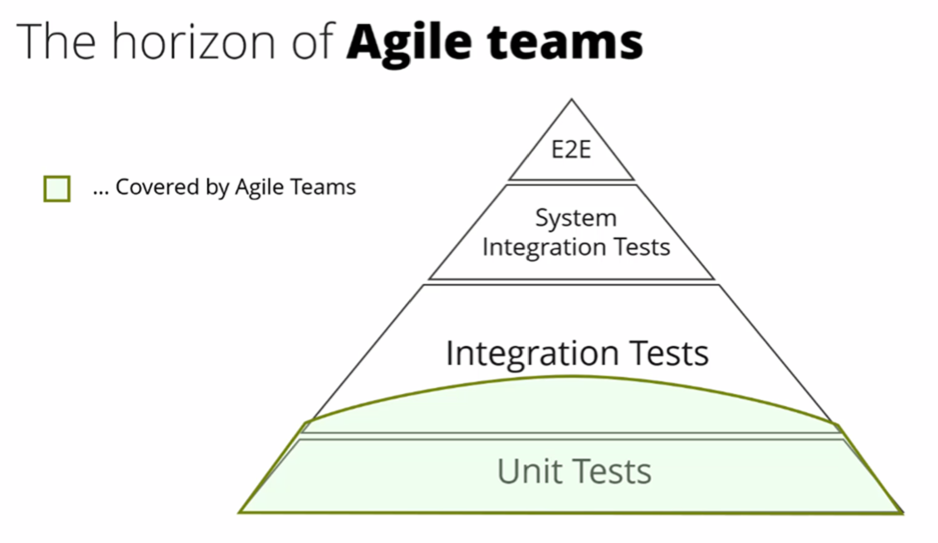

On Agile development teams, the party line is that unit testing is essential. It’s the most efficient way to expose implementation errors as they’re introduced. You can feasibly cover each function/method when you test at this level, plus when a test fails, you know exactly what function is broken. Moreover, having a suite of effective unit tests establishes a safety net that alerts the team whenever changes break previously-verified functionality. Those are just a few of the reasons why unit testing forms the foundation of the Agile test pyramid.

But, if you talk to developers in a casual setting, the truth starts to come out. Unit testing requires a lot of work, and they’re skeptical about whether it pays off. Just skim through a few of the 2.5 billion results returned by a Google search for “Is unit testing really worth it?” to get an idea of some of the issues.

Unfortunately, a seemingly endless amount of work is required to ensure that unit testing delivers long-term benefits as a regression testing safety net. Developers are committed to progression testing, not regression testing. Although developers on Agile teams usually write unit tests to check new functionality, few keep them up to date as the code base evolves. As the team moves on to another sprint, these tests become regression tests. Then, little by little, they start failing—but developers have moved on. The number of working unit tests at the base of the Agile test pyramid erodes, as does the level of confidence the test suite once provided.

In fact, data from our internal studies on financial instructions across EMEA shows that as an iteration ends, unit tests cover about 70% of the new code. After a few iterations of code getting extended, refactored and repaired, the original unit tests provide only about 50% coverage of that original functionality. This drops to 35% after several more iterations, and it typically degrades to 25% after six months.

Is Unit Testing Doomed?

Is Unit Testing Doomed?

Ultimately, developers don’t have the time or desire to keep these tests current over the long term. Unit testing has been a best practice for more than 20 years, yet despite waves of unit test automation tools (including one created by Albert Savoia not long before he declared testing dead), unit testing remains a thorn in developers’ sides. Does that mean we give up the benefits of unit testing altogether? Not necessarily.

In order to take on unit testing per se, testers would need to understand the developers’ code as well as write their own code. That’s not going to happen. But, you could have testers compensate for lost unit test coverage through resilient tests they can create and control. Professional testers recognize that designing and maintaining tests is their primary job and that they are ultimately evaluated by the success and effectiveness of the test suite. Let’s be honest, who’s more likely to keep tests current, the developers who are pressured to deliver more code faster, or the testers who are rewarded for finding major issues (or blamed for overlooking them)?

Another option is to consider new testing approaches that achieve unit testing benefits for today’s most popular development architectures—but without requiring knowledge of the code. Enter microservice contract testing.

Microservice Contract Testing: The New Unit Testing

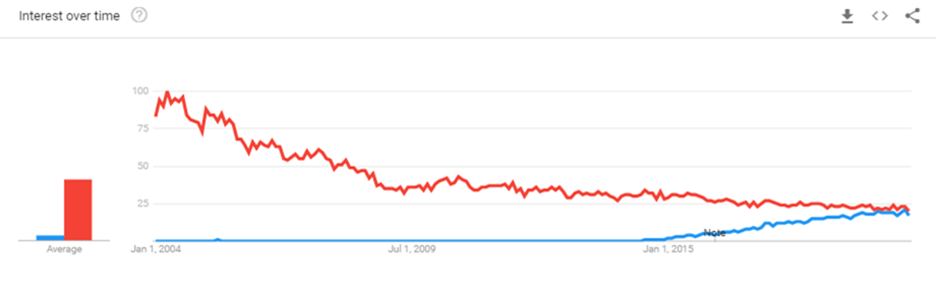

Interest in microservices (the blue line on the graph below) has been rising rapidly since 2015. In fact, it seems to be on the exact opposite path from software testing (red line).

This rise is hardly surprising. From the architecture perspective, there are significant benefits to microservices. Initial forays into service-oriented architectures (SOA) were a huge step forward in enabling reuse and flexibility. Business logic formerly implemented in monolithic applications was freed and released as isolated independent services, which were loosely-coupled and highly-distributed.

This rise is hardly surprising. From the architecture perspective, there are significant benefits to microservices. Initial forays into service-oriented architectures (SOA) were a huge step forward in enabling reuse and flexibility. Business logic formerly implemented in monolithic applications was freed and released as isolated independent services, which were loosely-coupled and highly-distributed.

Microservices take the decoupling and granularity to new levels. Business logic is now implemented in the smallest, most discrete units possible. Functionality that would have once been a single service is now distributed across tens, or potentially hundreds, of microservices, each of which can be independently developed and deployed.

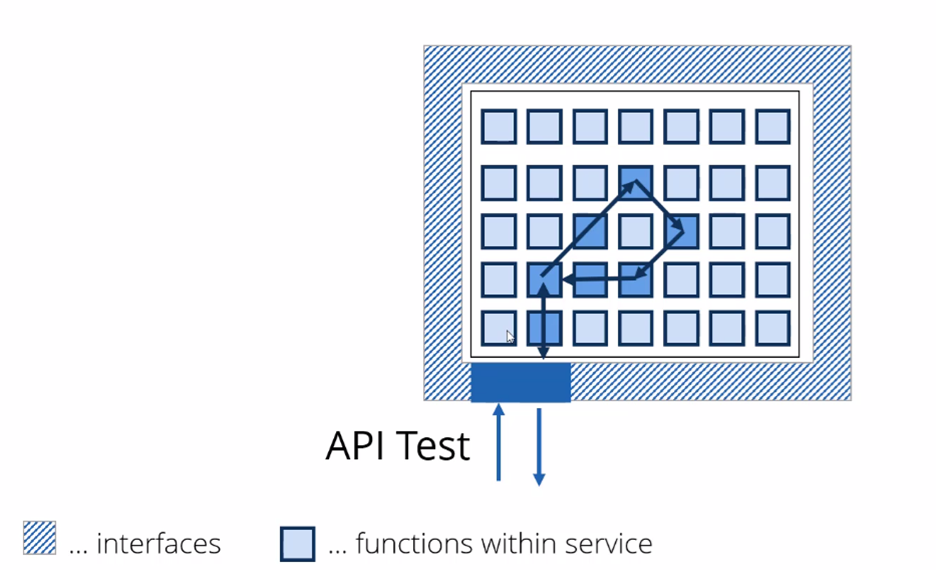

In addition to enabling unprecedented agility and scalability, this extreme decoupling opens up promising new options for testing. With the initial waves of services and APIs, API tests had little choice but to pass through a fairly broad set of business logic, which was likely implemented through multiple units of code (e.g., functions).

If an API test failed, there was no clear pointer to what specific code function needed to be fixed. That required unit testing and/or additional debugging.

If an API test failed, there was no clear pointer to what specific code function needed to be fixed. That required unit testing and/or additional debugging.

Now, with each microservice implementing an extremely focused unit of business logic, you know exactly what code is broken when an API test fails. Why spend the time and effort on unit testing if you’re already getting the benefits from something that’s considerably less painful?

Now, with each microservice implementing an extremely focused unit of business logic, you know exactly what code is broken when an API test fails. Why spend the time and effort on unit testing if you’re already getting the benefits from something that’s considerably less painful?

You might be thinking, “Testing hundreds of independently-evolving microservices is just going to present a different pain.” Correct. Each integration point is a potential point of failure, and testing all the possible integrations is a logistical nightmare—so don’t. Instead of testing how each microservice interacts with all the other microservices it touches, perform contract testing instead.

Very basically, contract testing helps both microservice consumers and providers ensure that they’re meeting expectations in terms of message format and data. The microservice consumer adds a contract that specifies expected request and response pairs for its various interactions with other microservices. Each contract is used to create a virtual service that the consumer can then test against. If the consumer’s changes result in incorrect/unacceptable request messages, they’ll be alerted immediately by a contract failure message triggered from the virtual services.

Very basically, contract testing helps both microservice consumers and providers ensure that they’re meeting expectations in terms of message format and data. The microservice consumer adds a contract that specifies expected request and response pairs for its various interactions with other microservices. Each contract is used to create a virtual service that the consumer can then test against. If the consumer’s changes result in incorrect/unacceptable request messages, they’ll be alerted immediately by a contract failure message triggered from the virtual services.

On the flip side, the microservice provider can use the same consumer-specified contracts to ensure that their own changes don’t break the functionality which consumers depend on. If the actual provider response suddenly fails to meet consumer expectations, they, too, get a rather clear and telling contract failure message.

The beauty of this approach—even beyond the fact that neither consumer nor provider ever has to stand up the whole spider web of interconnected and independently-evolving microservices—is that you get very specific unit-level failure information without burdening developers. As soon as testing moves away from the code level to the API level, it doesn’t need developers doing it. You certainly don’t need developers to deal with the maintenance, and you really don’t even need them to set up the test. Instead, the task can be delegated to people who view testing—not development—as their profession. We call them testers.

Looking Beyond Unit Testing Is Essential for Ensuring a Positive User Experience

Nevertheless, hyperfocusing solely on unit testing of any flavor can leave you blind to many critical issues. For example: Does every step of the end-to-end transaction work as expected—from whatever mobile or browser interface the user happens to have, through the backend (which might interact with custom/legacy applications, packaged applications, mainframes, databases, third-party services, etc.) and back to the user? Will these same transactions perform acceptably under a sudden increase in demand? If the user exercises the application in ways that the developers didn’t anticipate, will the application respond in a reasonable manner, or at least fail gracefully?

The answers to such questions lie beyond the horizon of the testing performed by the typical Agile team, which rarely extends beyond unit testing and a little integration testing.

However, as organizations invest millions in digital transformation initiatives, this doesn’t cut it. Maximizing that investment requires a flawless user experience from start to finish, 24/7. Professional testers thrive on exposing the glitches that developers tend to overlook but that would cause a CIO to cringe.

However, as organizations invest millions in digital transformation initiatives, this doesn’t cut it. Maximizing that investment requires a flawless user experience from start to finish, 24/7. Professional testers thrive on exposing the glitches that developers tend to overlook but that would cause a CIO to cringe.

I’m confident that software testing will surge in importance in the 2020s if we commit to expanding its scope and effectiveness, which will ultimately elevate its business value. As the pendulum swings back, testers can’t expect to just hang on for the ride. Willingness to jump on the momentum of this decade’s trends—for example, stepping in to solidify the foundation of the Agile test pyramid and embracing new practices such as microservice contract testing—will be essential for navigating the turnaround.