This is part three of the series, Tales of DevOps Discovery. To catch up, Read part one and part two.

In preparing for a DevOps transformation a critical first step is to perform upfront discovery, often asking even the most fundamental, seemingly obvious, questions of stakeholders. The major portion of such discovery should be done in a group setting. Asking stakeholders these fundamental questions in a group setting can provide key insights into differing perspectives and even differing objectives regarding a planned DevOps implementation. Sharing these different perspectives during the discovery phase sets the stage for mutual empathy and enables stakeholders to identify and align, an important step to aligning on shared objectives. In this article we will outline common questions asked, share real-world answers and offer guidance on interpreting and applying the results.

Discovery Question: What do you want to achieve with this transformation/DevOps?

One of the first things to consider is, “Why are we doing this?” as this establishes the goals and objectives. Accordingly, I usually begin by asking the stakeholders during discovery what they expect to achieve through the transformation to DevOps. The answers I receive to this question often differ distinctly, depending on the role of of the person answering. Understandably, they are heavily influenced by the unique perspective of that role.

Answers:

CIO: “We want to increase our ability to “scale-up” delivery as we shift to a primarily SaaS (software-as-a-service) model and see a rapid increase in business. These means we have to increase developer productivity, and respond to customer requests faster, all while reducing our number of Severity #1 issues.”

Operations:

“We want to reduce technical debt, to minimize firefighting and increase our ability to adopt modern best practices such as Infrastructure-as-code. We have to be able to keep the lights on while delivering applications to production.”

Development:

“We would like to minimize customer-specific one-off work, which is resulting in painful complexity in development, QA (quality assurance) and deployment, and is an overall source of inefficiencies. We would like to be able to spend more time improving user experience, performance and increasing valuable functionality. But, instead, we are chasing bugs and reworking misunderstood requirements.”

Guidance:

Not surprisingly, executives often respond with a focus on business-oriented goals such as increased productivity and customer response, while Operations focuses on stability and minimizing firefights and Development wants to innovate. But within these differences we see some commonality that can be harnessed, such as productivity. For example, one point of commonality is productivity:

CIO: “We have to increase developer productivity.”

Operations: “… minimize firefighting and increase our ability to adopt modern best practices …”

Development: ” … spend more time improving user experience, performance and increasing valuable functionality.”

Another point of commonality in the CIO, Development and Operations answers is the focus on quality:

CIO: “ … reducing our number of Severity #1 issues.”

Operations: “We want to reduce technical debt … keep the lights on …”

Development: “… instead, we are chasing bugs … ”

These points of commonality can be used to establish common goals with cross-functional buy-in, such as:

- Our effort will result in increased productivity and minimize overtime and firefights (across teams)

- Our efforts will result in increased application quality and uptime

They then can be used not just as driving principles that inform decisions such as process or tool choices, but also to establish key performance indicators (KPI), which will be used to quantifiably measure success of the transformation. Example KPIs may be:

- Reduction in cycle time, from story acceptance to user acceptance (or release)

- Number of Severity 1, or Severity 2 production issues per release

- Defects per build

- Defects per release

- Hours worked by Development? Operations?

Discovery Question: Do you practice agile today? If so, how do you define done for a story or sprint?

Continuous delivery (CD) and lean practices are foundational to a successful, sustainable DevOps transformation (though not required to meet the some definitions of DevOps.) If we look at CD and lean practices as a pipeline through which we need to manage a continuous flow of changes represented by work, then it is important to consider what work is sent into the pipeline, how the work is initiated and how the changes are managed. Accordingly, it is important during discovery to ask customers high-level questions about development methodologies used and overall practices for definition, planning and coding.

The answers given vary between different levels of, “Yes, we are agile,” “No, we are waterfall,” and, “We practice both.” Most Most often, organizations’ answers describe adherence to a form of agile with room for improvement.

Answers:

“We practice agile and/or scrum. We work in two-week iterations, planning the work for a sprint at the end of the prior sprint.

We consider a story done once the code has successfully been committed and merged to a team branch, and is successfully built. We consider a sprint complete when all stories for that sprint are committed and successfully built.

“Roughly every three months we integrate code from team branches to trunk and perform a mix of automated and manual regression and acceptance tests. Once the build passes QA we manually deploy to preproduction environment, validate and schedule a manual deployment to production.”

Guidance:

This is a classic story of agile adoption in traditionally waterfall organizations. The organization adopts agile within Development without involving other key functional teams such as QA or Operations. Usually, this is because it simply is easier. There are a number of obstacles to overcome in extending agile practices across organizational, technical and cultural boundaries, so the obstacles are avoided by limited the agile adoption to these boundaries.

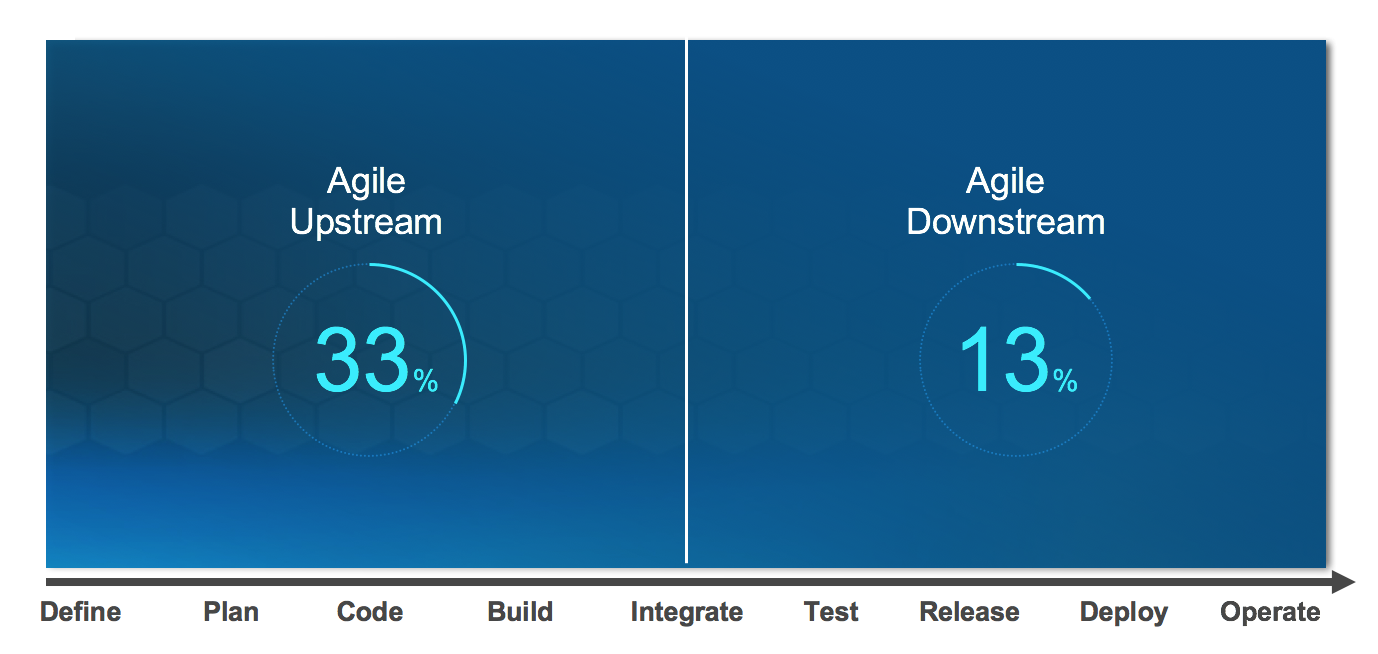

This is a case of confining the adoption to “agile upstream” while practicing waterfall or legacy “downstream.” Studies show that less than 33 percent of organizations have adopted “agile upstream” and exercise agile or iterative development practices for the planning, coding and team builds, yet only 13 percent of organizations have adopted agile downstream, and follow practices such as continuous integration (CI), CD, automated provisioning testing and deployment.

The negative effects of limiting agile adoption to agile upstream are multifold, but can be summarized as, “You never really know when you are done-done.” As a result, you cannot accurately measure progress, introduce deferred risks or disrupt the development plan to address issues found during the downstream portion of the process, such as poorly understood requirements surfacing during acceptance testing or runtime issues discovered during deployment to a production-like environment or, in the worst case, issues found in production by the end user.

A seminal book on DevOps is, “The Phoenix Project,” by Gene Kim, which presents three ways of DevOps thinking. The first way, “Systems Thinking,” addresses to this gap between agile upstream and downstream, Dev and Ops, business and customer by taking a systems view across the traditional boundaries and establishing “flow” of the system through the boundaries.

Discovery Question: Do you practice CI today? What types of validation do you perform?

As CD is foundational to DevOps, CI is foundational to CD. CI can be scene seen as the connection point for agile upstream to agile downstream, and the pump that fills the CD pipe. It is both the practice most organizations say they follow and the practice that most often is implemented incorrectly. So when surveying a customer’s current state during discovery, it is important to know whether CI is currently part of the picture.

Answers:

“Yes, we practice continuous integration. Each team has a Jenkins CI server. Developers commit their changes multiple times per week. Jenkins then builds the changes as part of a nightly build.”

“We do some unit testing, but we do not track code coverage. If the nightly build fails we may continue to commit, but we usually fix the issues within a few days.”

Guidance:

This is a common answer and an example of how CI can be improperly implemented. CI is more than having a shared Jenkins CI server and running scheduled builds. CI can be defined as:

“A a software development practice where members of a team integrate their work frequently, usually each person integrates at least daily – leading to multiple integrations per day. Each integration is verified by an automated build (including test) to detect integration errors as quickly as possible.” — Martin Fowler

The benefit of practicing CI includes identifying integration and quality issues close to the source of the issue, thus reducing the time to correct and enabling higher-quality software to be developed more rapidly.

Essential elements of properly implemented CI are :

- Integrating changes frequently, ideally multiple times per day or even per change.

- Performing consistent validation of quality through component level testing, code scans, etc.

- Always maintaining a working build, suspending development when a build fails, and not resuming development until the issues is corrected or reverted.

Teams that allow a broken build for “a few days,” deferring commit or builds to just “multiple time per week” or that do not validate consistently through testing practices are not practicing CI and will not yield the benefits of CI.