A research report published by Checkmarx finds the same basic malicious software developed using multiple programming languages as cyberattackers industrialize their malware development processes.

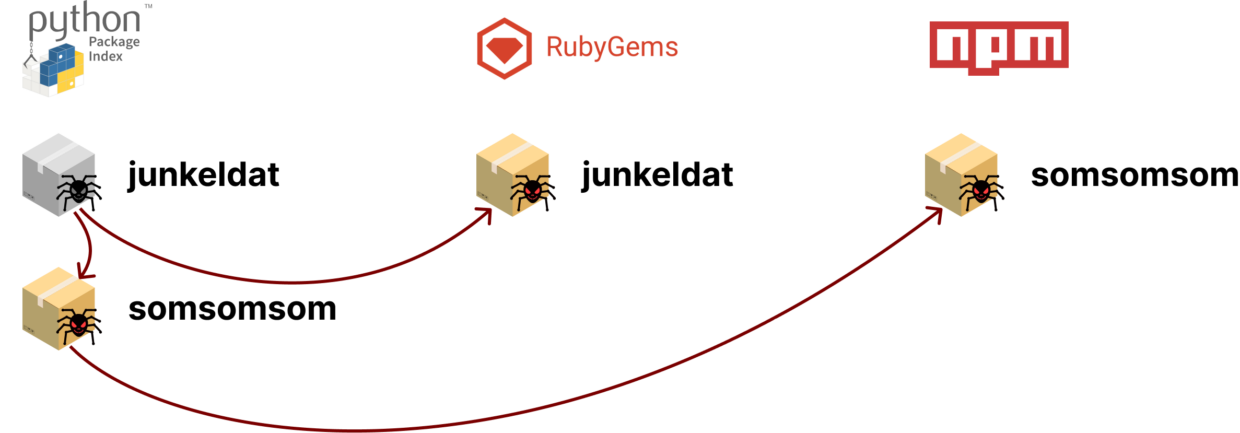

Checkmarx, a provider of code scanning tools, shared examples of malicious packages written in multiple programming languages. These example packages share the same indicators of compromise that have gone undetected for years. A “junkeldat” PyPI package for Python applications, for example, that has been compromised also shows up in a Ruby version of the package.

Tzachi Zornstain, head of supply chain security for Checkmarx, said much like any other development team that uses multiple programming languages, it appears cybercriminals are also sharing techniques. These examples highlight the need for development teams to share security intelligence even if they build applications using different programming languages, he added. There is a tendency for development teams using one programming language to ignore application security issues that appear to only impact applications written in another programming language, noted Zornstain.

The fact that the packages remained undetected for such a long period of time is due—at least in part—to the lack of information sharing in the ecosystem, said Zornstain.

Cyberattackers are, of course, trying to take advantage of the implicit trust many development teams have in open source projects. However, now that more cybercriminals are making a concerted effort to compromise downstream software components, it’s imperative that every component be vetted, said Zornstain. In fact, organizations should not use any code provided by strangers, he advises.

The core issue is that many open source projects are maintained by a small number of programmers contributing their time and effort to building components that others are free to use. Many of them argue that the onus for making sure software is secure is on the organizations that decide to deploy that software. Nor is it their responsibility to keep track of cybercrimimals distributing malicious versions of their software.

Unfortunately, many IT vendors and large enterprise IT organizations that rely on that code are, unfortunately, not contributing anything meaningful back to the project, either in terms of financing or helping open source maintainers find and remediate vulnerabilities. Many of those same organizations, however, are assessing whether the open source software they employ is, from a security perspective, actually sustainable in the absence of those contributions. As a result, it may be only a matter of time before these long-simmering open source software security concerns boil over into a larger crisis.

One way or another, DevSecOps best practices will need to be applied to application development at a deeper level. Organizations can’t assume that the software components they are relying on have been scanned for vulnerabilities by someone else. It’s simply too easy for a development team to make a mistake. The need for higher levels of security may lengthen the development process, but the alternative—malware infestations wreaking havoc—is far less desirable.