Has automation changed the way we perceive interaction with others?

A few weeks back I got an email from an old friend, Jim. Typically, that’s no big deal; I get emails from old friends all the time. Except, in this case, it was different. According to a posting on Facebook, Jim passed away about a year ago.

Another friend who is still among us reports having a similar experience of receiving emails from those who are dead. It’s an eerie event that’s becoming more common. Bad actors hack into a data store and pull up some email addresses, which they blast about nefariously to unsuspecting recipients. It’s a strange, almost morbid experience when you’re on the receiving end.

But it’s gotten me thinking: What does it mean to be alive on the internet? And, more importantly, how much of what we perceive on the internet as a human really is? Jeepers—for all I know, the Facebook post could have been a ruse. Maybe Jim uploaded his consciousness into eternity and he really is trying to make contact. How would I know it otherwise?

Allow me to elaborate.

Technology that Captures the Moment

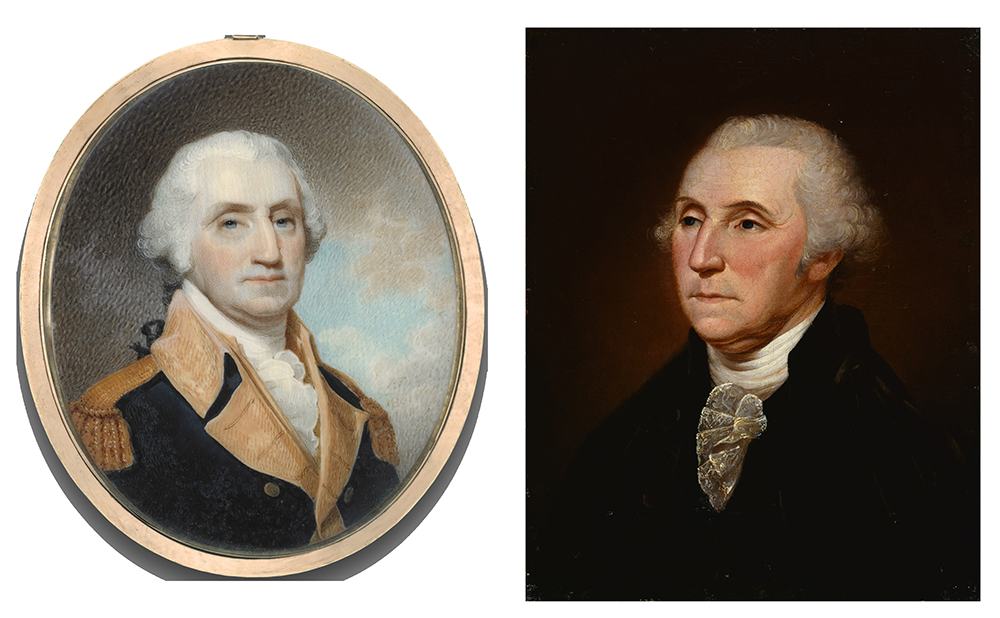

Mankind has been using technology to represent reality since early caveman figured out how to draw pictures of hunters and animals on the walls of caves. The more real a depiction seemed, the more valuable it was. A sign of significant wealth was having the wherewithal to pay an artist to paint your portrait. The painting passed your likeness onto future generations. Your posterity knew what you looked like. The poor just drifted in away into imageless anonymity.

However, whether you were rich or poor, there was one thing that technology couldn’t do: It couldn’t capture the moment. A painting took weeks, maybe months to complete. And, no matter what, the rendering was an interpretation.

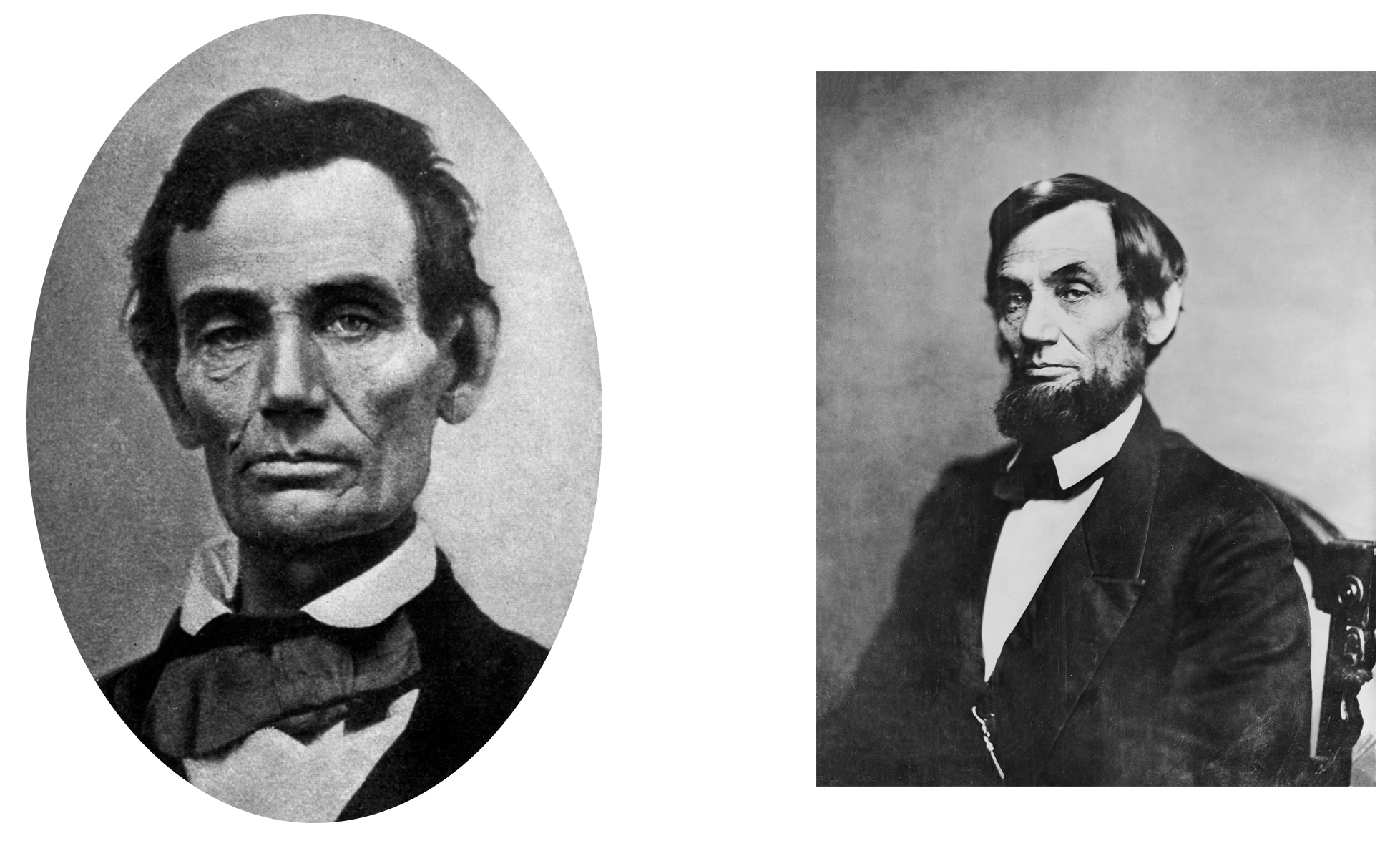

Photography changed all that. It captured the moment, which was a first in human history. And it democratized portraiture. In practically no time at all, it seemed that just about every town and city had a photography studio. Affordable photography made it so images of mothers and fathers could be passed on—future generations had a very clear idea of what great-great-grandma Mary and grandpa William looked like.

Portraits of George Washington left a lot to the imagination. Photographs of Abraham Lincoln left no doubt.

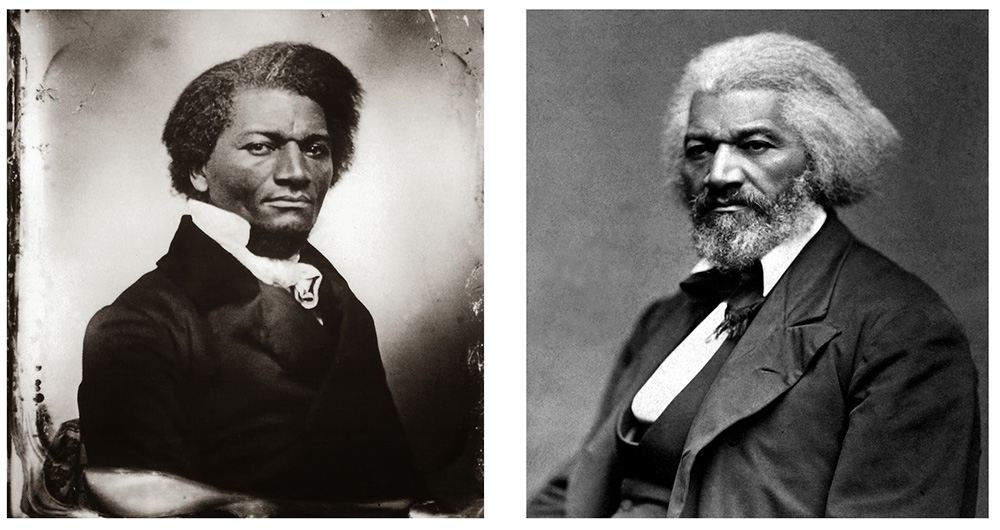

The first time that 19th century former slave, abolitionist and author Frederick Douglass had his photograph taken was in 1841. By the time of his death, he was the most photographed man in America. Douglass understood the power of the technology both in terms of information representation and dissemination. Photographs of Douglass made his humanity real at a time when a good portion of the population of the United States was deemed subhuman.

The power that photography brought the technological and cultural landscape created trust in the image. The veracity of information in a newspaper article could be argued, but the image the camera captured represented reality beyond a doubt—at least until the practice of doctoring photos to misrepresent reality came into practice.

Reincarnation as Seen on TV

And then came television, which made it possible to represent reality as a stream. Whereas a photograph captured the moment, television captured as many moments as the viewer had to spare. But, it was a trade-off. Television distorted perceptions of life and death. Before TV, no child ever had the experience of viewing an actor portraying a character who died in an episode of “Gunsmoke” one week, only to reappear as another character on another TV show the following week. Death became impermanent. Also, the line between fact and fantasy blurred. The same television screen that brought the nightly news also delivered episodes of “Star Trek.”

In terms of time and space, the only “real” thing is the TV set. Everything else is content. Sometimes you could tag the content as “fact” and other times as “fiction.” Or, you could tag it to a third category, “I’m not sure,” which gave rise to the harebrained idea that the 1969 moon landing really happened in a TV studio at a secret government location.

Now, here’s where it gets really interesting. In the past, most people interacted with others most of the time in close proximity. You went to Grandma’s house for the holidays. You bought your groceries at the neighborhood supermarket. You sat in classrooms under the supervision of one or many teachers for at least 12 years, maybe more.

That was then and this is now.

Today, visiting Grandma for the holiday might be nothing more than a call on Skype. More people are making essential purchases online. The online class is replacing the brick-and-mortar school building.

The fact is, we’re spending a lot of time in an environment that is essentially representational. Every day, more of our interactions with the “world” take place on the screen of a smartphone, tablet or a desktop computer. In some cases, it’s nothing more than talking to a device by name, as in “Alexa, what time is it?”

Is it Human? Does it Matter?

And thus we have the problem of distinction. We’re at the stage now where we’ve come to accept that some of the interactions we have online might be with a human and some interactions might be with a machine powered by AI. Sometimes it’s easy to tell. After all, I know there’s is no miniature person living inside my Echo device. And I know there is no little man inside my refrigerator who turns on the light as I open the door. This is low-hanging fruit; it’s obvious what the machine is. Still, in the long run, how can we tell? And, even if we can’t, does it matter?

These days I have a lot of interactions with people on video conference and on the phone. I estimate that of all the people I interact with regularly, I’ve shaken the hand of about half. Twenty years ago, I physically touched nearly all. Such is the way of progress.

I’ve had the benefit of living in a time in which the person came before the photograph. Now, we live in a time in which the photograph can come before the person. We think up the ideal actor and send it over to the special effects department for rendering. Today, we interact with images that have no human origin and yet behave in a way that is indistinguishable from a human. For those born today, it’s entirely possible that most of the meaningful relationships they have throughout their lifetime will be with non-human intelligence. Yes, there is a good argument to be made that people will still gather together in real time for concerts, religious services and sporting events. But consider this fact: 73,000 people attended the 2018 Super Bowl in a stadium, in real time. However, 103 million watched the event on TV. The “attendance” at the digital representation of the event exceeded the real-time experience by more than a factor of 10. And, companies paid millions of dollars for advertising time during the televised game. Today, that which we perceive as real is just as meaningful as that which actually is real.

Which brings us to life and death in the age of automation. Unless Kurzweil proves right and uploading ourselves to a computerized host becomes possible as the Singularity approaches, all of us will die. And yet the images, both the ones we make and the ones that were made for us, will live on forever. Will these images take on a life of their own? Will we be able to use artificial intelligence to inject these images with the behavior that made us us, using information about us that was gleaned by observing every aspect of the online interactions we had over our lifetime?

I’m not sure. But the possibility has stopped me from replying to that latest email from my friend, Jim. To be honest, I’m afraid of what would happen if I did.