There was much excitement in the air when the announcement that Docker had acquired SocketPlane. Not the least of which was emanating from my corner of the world, where DevOps for network (the whole network) is something you’ve noticed I pretty much live and breathe.

The announcement was couched as an SDN (Software-Defined Networking) play by containerization-leading Docker. Which might be confusing at first because, well, Docker (and to be more general, containers) are generally associated with DevOps, not SDN.

Ah, but therein lies the rub, doesn’t it? While the original precepts of SDN were most definitely not DevOpsy in nature, it (like every other trendy term in tech) has evolved to focus as much (if not more) on what are certainly DevOps-like principles and goals than on technical specifications and standards.

Consider, for example, this recent Avaya sponsored, Dynamic Markets report (gated) on “SDN Expectations.”

The first data point to examine is the ranking of “problems” experienced by respondents. The number one issue (38%) was downtime caused by human error. The second (tying with a network-failover issue at 37%) was complexity of configuring services and applications across the network.

If these aren’t typically problems that are said to be resolved by DevOps – particularly with attention paid to collaboration and automation – I’ll eat my hat. And yes, I often wear hats, it’s a quirk I have.

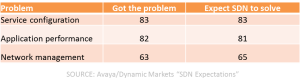

And just as interesting was this table illustrating not just problem areas, but how many respondents had the problem and how many expected SDN to solve them:

If you ignore the network management tuple, the top two problems are definitely often associated with DevOps as issues that can be resolved with collaboration and automation and some measurement thrown in to boot.

SDN has evolved, at this point, to focusing more on network automation than it does on automated networks. The difference is actually profound as it relates to DevOps, as the former is really about  management, about configuration and provisioning and automation of processes designed to extend CD across the entire application deployment lifecycle into the production environment. It’s about codifying and encapsulating configurations in templates and centralizing state of the network in order to engender better agility in both moving forward and falling back when things go awry.

management, about configuration and provisioning and automation of processes designed to extend CD across the entire application deployment lifecycle into the production environment. It’s about codifying and encapsulating configurations in templates and centralizing state of the network in order to engender better agility in both moving forward and falling back when things go awry.

SDN today really is (or should be) a subset of DevOps, focusing on network infrastructure operations rather than app infrastructure operations. But the same principles and goals are very much aligned between DevOps and SDN, between the network and the application infrastructure. That’s a critical convergence starting to appear that’s necessary, as when you dig into IT and its problems delivering apps on time these days, it’s mostly the network that’s still in the way.

The network is identified often as a key IT pain point and usually the pain is related to the provisioning of services and applications across the network. High costs of networking is also cited, and that is largely due to the complexity of the network and the amount of operational sweat and blood that goes into manually provisioning, configuring and testing the various pieces of network infrastructure required to deploy the services business needs to deliver applications.

SDN may continue to be referred to as SDN, if only to emphasis its focus on network infrastructure, but the reality is that it’s DevOps. DevOps for Networks.

Which brings us right back to why a DevOps-related, containerization company like Docker would swallow up an “SDN”-focused start-up like SocketPlane.

Because what IT expects from SDN is really DevOps. And if DevOps is ultimately about culturally change and breaking down silos, the folks who focus on the network can’t be (and shouldn’t be) isolated from the folks managing the application infrastructure.

Docker’s move brings software-defined networks together with software-defined operations under (what should be) an IT encompassing concept: DevOps.