I’ve been interested in the ramification of automation on human employment for a while now. My profession, IT, is bringing more automation to the planet every day. I would be irresponsible to not understand the ramifications of my work.

Recently in my research I came across three facts that gave me pause. The facts are:

- Due to improvements in automation, it takes fewer people to create more goods and services.

- We are producing more good and services than we ever have, possibly more than we might ever need.

- Just as it takes fewer people to create goods and services, fewer people are garnering more of the wealth being created.

The implications of these facts are dramatic and the implications are far-reaching. Allow me to elaborate.

Fewer People Create More Output

Consider this fact: In 1790 90 percent of the people in the United States were engaged in agriculture. Most of the people fed the population. Two hundred years later, 2.9 percent of the population was engaged in agriculture. A relatively small amount of people create enough food for all.

Also, consider this one: In 1980 it took 26 people to create a $1 million in output. Today it takes 2.6.

The pattern is obvious. As time marches on, it takes a lot fewer people to create a lot more wealth. Why? Automation technology. Every year we create more hardware and software that does work previously done by humans. Automation never tires and produces as much as we want, when we want. The trend is strong and consistent. The rate of innovation is increasing. And as the rate increases, more people will be displaced by machines and software. I talked about this extensively in the first article I wrote in this series.

Let’s move on.

We’re Producing All We Want — and Then Some

Today China, India, Brazil, Vietnam, Indonesia, Pakistan, Thailand, Mexico, Italy and Turkey combined produce 18.5 billion pair of shoes year. That’s more shoes made a year then there are people on the planet. (The current population worldwide is 7.5 billion.)

Today there are 260 million cars registered in the United States, which comes out to a little more than one car for every adult in the population.

The number of cellphones in China in 2014 is 1.14 billion, in India there are 1 billion and in the United States there are 327 million. Just about everybody in these countries has a cellphone. And the prices keep dropping. Eventually, everybody on the planet will have a cellphone—which, by the way, has more computing power than did the computers onboard an Apollo spacecraft.

Productivity no longer is constrained by the capacity of human labor to create goods. Whereas before the Industrial Revolution not enough goods were produced to satisfy consumer demand, today things are reversed. The modern struggle is finding enough buyers to purchase what’s been made.

As I mentioned earlier, we’re really good at making as much as stuff as we want, whenever we want. And yet, despite this abundance, there is a problem.

Wealth is Concentrated to a Few

A report that came out earlier this year reveals a troubling fact: Eight people on Planet Earth own as much wealth as 50 percent of the rest of the global population. True, there is some dispute going on about the methods by which this number was determined. But, even if the number is 30 percent, the disparity in the distribution of wealth is astounding. More wealth is being concentrated to fewer people even as automation becomes more prevalent. Abject poverty may not be rising, but increased displacement of workers is. As workers become displaced, their wealth diminishes.

Saying “Things must change” is absurd. Things will change. The question is, “What will that change look like?” Will we have a fully automated society in which there are more than enough shoes to go around, or will we still have a world in which there are those that go shoeless?

What Do We Do Now?

In previous articles I’ve talked about Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a possible way to address the problem of providing income for displaced workers. UBI is a viable solution, but not one that will to come to fruition in the near future. The problem is here today. So, what do we do?

Read on.

Economic Sustainability Over Economic Growth

I’ve mentioned many times, there is a good argument to be made that the jobs taken away by automation are not coming back, nor will there be an abundance of new jobs to replace those taken. My prior article supports my assertion. Eighty-eight percent of job displacement is due to automation. The need for human labor is diminishing at accelerated rates. That’s the bad news. The good news is that automation has allowed us to grow our productivity more than we’ve imagined possible. But growth is not the answer. On a planet full of shoes, there are still those who go shoeless. The change we need to make is to move from an economy based on growth to one based on sustainability.

Changing the Way We Talk About Things

I’ve come to accept that we cannot grow our way into economic prosperity any more than we can grow our way into good health. In fact, too much growth can kill you—just ask someone who suffers from morbid obesity. So I made the change in how I talk about prosperity. I no longer use the term “economic growth.” Rather, I use the term “economic sustainability.” I am a big believer that thinking follows language. Change the way we talk about something and we’ll change the way we think about that thing. If we want to have a sustainable economy, we need to start talking that way.

Creating Wealth for All

Okay, I’ll come clean. I think that given the current trends, too few have too much. More wealth parity is required. But, as we have learned on the terrain, overt wealth redistribution is not the answer. We cannot tell somebody we’re going to take away a part of their wealth without upsetting them. But, we can set an example in the benefit of sharing the wealth to benefit all. We in IT have been doing it for years—it’s called open source. We learned a few years back that when we give it away, we get it back. The trick now is to go beyond IT and make the open-source mindset part of our civic sensibility.

At some point in the not-too-distant future—say, about 20 years—we will be at almost total automation. If trends continue, there will be few with a lot and a lot with a little. People that don’t have a lot don’t have much to lose. Wealth inequality creates turmoil, unrest and overt aggression. If you think not, take a look at the excesses of France under Louis XIV which, by the time you got to Louis XVI, led to the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror. Or consider that the wealth disparity during the last generation of the house of Romanov led to the Russian Revolution. Nicholas dined in lavish halls while the serfs starved. Lenin prevailed.

Wealth parity creates political stability and political stability creates prosperity for all. Achieving wealth parity comes about by sharing. Again, we who have code on GitHub know this. Again, the trick is to make the open-source dynamic part of our civic sensibility.

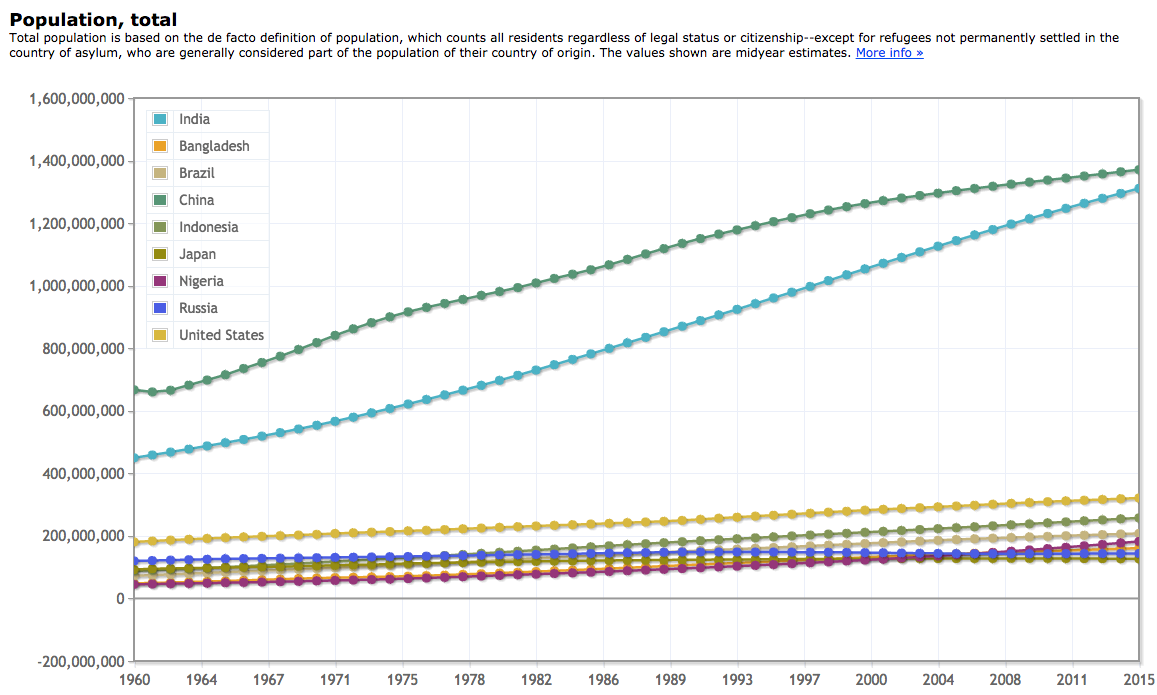

Let me close by providing one more fact. One of the thing I’ve learned in my research is that as the population rises in a country, so does the GDP.

Figure 1: Population growth among 9 most populous countries, 1960 -2015 (Source World Bank)

Figure 1: Population growth among 9 most populous countries, 1960 -2015 (Source World Bank)

Figure 2: GDP Growth, 1960 -2014 (Source World Bank)

Figure 2: GDP Growth, 1960 -2014 (Source World Bank)

But, again the trend is that the wealth goes upward to a few. So we have a choice. As automation increases, we can learn to share the wealth and create a world that is stable, sustainable and prosperous. Or we can keep the current trend in place, allowing the few to have the most. And because we don’t need a lot of human labor to maintain the levels of production possible, rather than risk ongoing political upheaval and civil unrest, we can just get rid of those that unfortunately are on the wrong end of the distribution curve. Their labor is no longer needed.

Is such an idea vile and extreme? Yes, it is. Is it one without precedent? I’ll let you be the judge.