Giving automation the power to detect crime and enforce punishment has ramifications, even for minor infractions

In November, I broke the law. I crossed over a solid white line to make a right turn at a traffic intersection. At the time I was unaware of my violation. I was on my way to a shopping mall in an unfamiliar part of town to buy my wife a gift for her birthday. My only defense is that I was following the instructions emitted from the map app on my cellphone. It told me to make a right turn. So I did. Little did I know I was being watched.

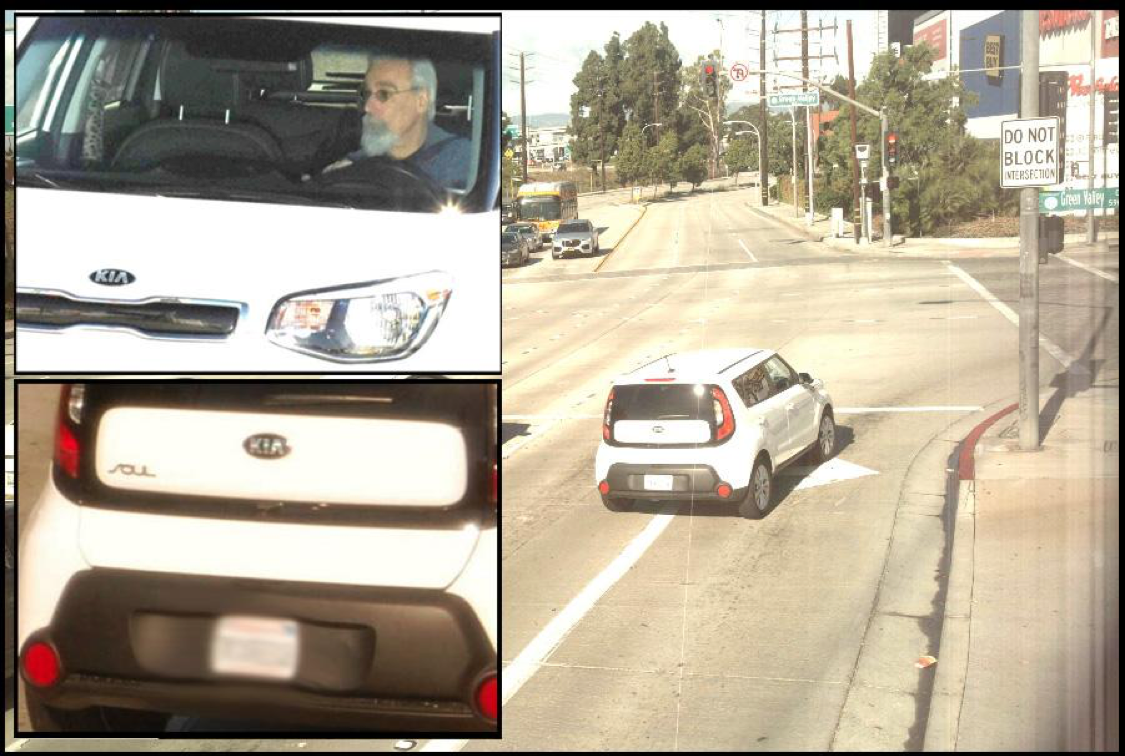

A few weeks later, I received a citation in the mail. The citation had photos of me, my car’s license plate and the car crossing the solid white line. Turns out, there were cameras at the intersection watching all traffic activity. I was busted. I was also a bit shocked: My experience getting a traffic ticket 10 years earlier involved a real police officer writing me up in real time. Now it was as if Big Brother was indeed watching.

In addition to the eerie feeling that goes with being charged with a crime anonymously well after the fact, I also felt baffled. The traffic citation did not list the amount of the fine I had to pay. The only information it provided was that I needed to go to the traffic court website to learn the details. So I did.

I logged into the website and entered my citation number. The site had no record of the ticket, but noted that it can take up to 30 days for an automated ticket to make it into the system. I felt powerless; I was charged with a crime, liable for a fine and yet didn’t know how much my transgression was going to cost me.

I decided to call the telephone number provided on the citation for more information. I dialed the number using the same cellphone that had gotten me into trouble in the first place. I was connected to an automated answering system. After navigating through various Yes/No and “enter the proper number” prompts, I learned that the system had no record of my citation. My only option was to wait 30 days for the systems to get their collective act together.

A month later, a formal citation did indeed arrive in the mail, noting the amount of my fine ($480) and options for payment. Also, the citation provided instructions to go online and pay the ~$500 required to attend traffic school, should I so desire. (Traffic school is an option in California in which you attend a one-day class about traffic safety and your violation is kept private from insurance companies. The result is, your automobile insurance rates don’t go up. Here in Los Angeles, a lot of professional actors teach traffic school as a side job. As you can imagine, traffic school can be quite entertaining. But, I digress.)

At this point, I was completely bewildered. I’d been busted for a crime I didn’t know I committed, by machines I didn’t even know were there. The only way I could get the details about my transgression was by interacting with other machines on the internet or on the phone. And, should I decide to plead guilty and settle matters, my first, best option is to do so via automation.

Still, the technology was failing me. I needed to talk to a person, any person. So I went down to the courthouse in Santa Monica. There I found a special window on the exterior of the courthouse building for processing traffic inquiries. (One of the nice things about living in sunny Southern California is that providing service outdoors throughout the year is a viable option.)

I waited in line. Finally, I got called forward to the window—which, by the way, was a pane of blackened glass. I had no way of knowing who or what I was talking to; all I saw was my reflection in the black mirror. A voice from the speaker at the bottom of the window asked me to state my business. I did. The conversation continued. The responses from the speaker seemed brusque, if not a bit preformulated. I started to wonder, Am I talking to a machine or a person? So I asked a random question, “How much is two plus two.” The voice in the speaker responded, “Sorry I am not programmed to respond to that information.”

Now I was really thrown. Was I confronting yet another piece of automation? After a minute or two, the voice in the speaker said, “I’m just messing with you. I get this all the time. They all think I’m a machine.”

It turns out that the voice did indeed belong to a human, and the human’s name is Dante Pipkins. Dante shared an interesting fact with me: Even though my violation was caught on camera, the actual OK to create the citation was issued by a human police officer behind the scenes. Go figure.

Thus, having been enlighted about the details of enforcing traffic law via camera, I finished my business by having Dante give me a date to appear in traffic court, before a human judge, to plead my case. I knew there was no way to proclaim my innocence. I had been caught red-handed. My intention was to throw myself on the mercy of the court to get a reduced fine.

The Power of Automation

Automation is a great thing. It empowers us. It saves us time and money. Without automation, there’s no AWS, Google, Azure, Digital Ocean, Netflix, Etsy, Shopify, Facebook, Instagram, Slack, Airbnb, New York Stock Exchange … the list goes on. Automation is more than a technological feature. It’s now a way of life. And, for those of us who work in DevOps, automation is fundamental—none of us want to go back to the days of manual deployment and guesswork system monitoring, to say the least.

Yet, we do walk a tightrope. As my recent travails with a very minor aspect of the legal system demonstrate, automation is becoming a key factor in everyday law enforcement. On face value, this might seem like no big deal, but consider this: Today, charging a citizen with a crime is still subject to some sort of human intervention. There are a lot of details to consider that go beyond the current capabilities of AI and machine automation. Human judgment is still the most reliable form of judgment. Yet, it’s time-consuming and expensive. Eliminating time-consuming, expensive tasks with cheap, fast, accurate machine-driven processes is a key motivator for using automation.

As automation becomes more familiar with the activities it is processing, it becomes an expert. And, as automation achieves expert status, it replaces human activity. Just think about detecting credit card fraud; these days, practically all of it is done using automation. While we still have a long way to go in terms of totally automated processes, automation is creeping its way into law enforcement. My recent experience is proof.

Now, imagine a world in which crimes such as tax evasion, financial fraud, embezzlement, regulatory non-compliance and yes, moving traffic violations are detected, reported and, most importantly, prosecuted using automation. Let’s go further: Let’s imagine that automation becomes the default method of prosecution. Imagine that the justice system becomes so automated that the defendant is presented with an offer to plead guilty to a sentence already predetermined according to an AI algorithm. Or, the defendant can choose to opt into a human interaction but will need to bear the burden of the increased court costs, very much in the same way that an automated audio transcription service charges extra for a human to do the work.

Is such a scenario possible? Well, think about this: My interactions around the traffic violation were conducted without me ever having once had to interact with a human being. I was guilty as charged and automation proved this beyond a reasonable doubt. Not only did the technology detect my transgression, but it also connected me to my car, thus making citation possible. Hence, there’s a good argument that, when it comes to automation-enabled law enforcement, the distance from catching misbehaving drivers in the act to actually going after real crooks is just not that far a leap.

So, what does this have to do with DevOps? When you scrape away all of the technological marvels, at some point there’s going to be someone in DevOps either creating, deploying or fixing the systems that make this all possible. It’s a big deal to give automation the power and technical wherewithal to enforce “the law.” As the feasibility of putting complex, comprehensive law enforcement systems into play increases, are we in DevOps going to consider such deployments as just another day in the CI/CD pipeline, or are we going to think through the game-changing impact of what we’re about to make?

For now, I’ll leave it up to you to decide.