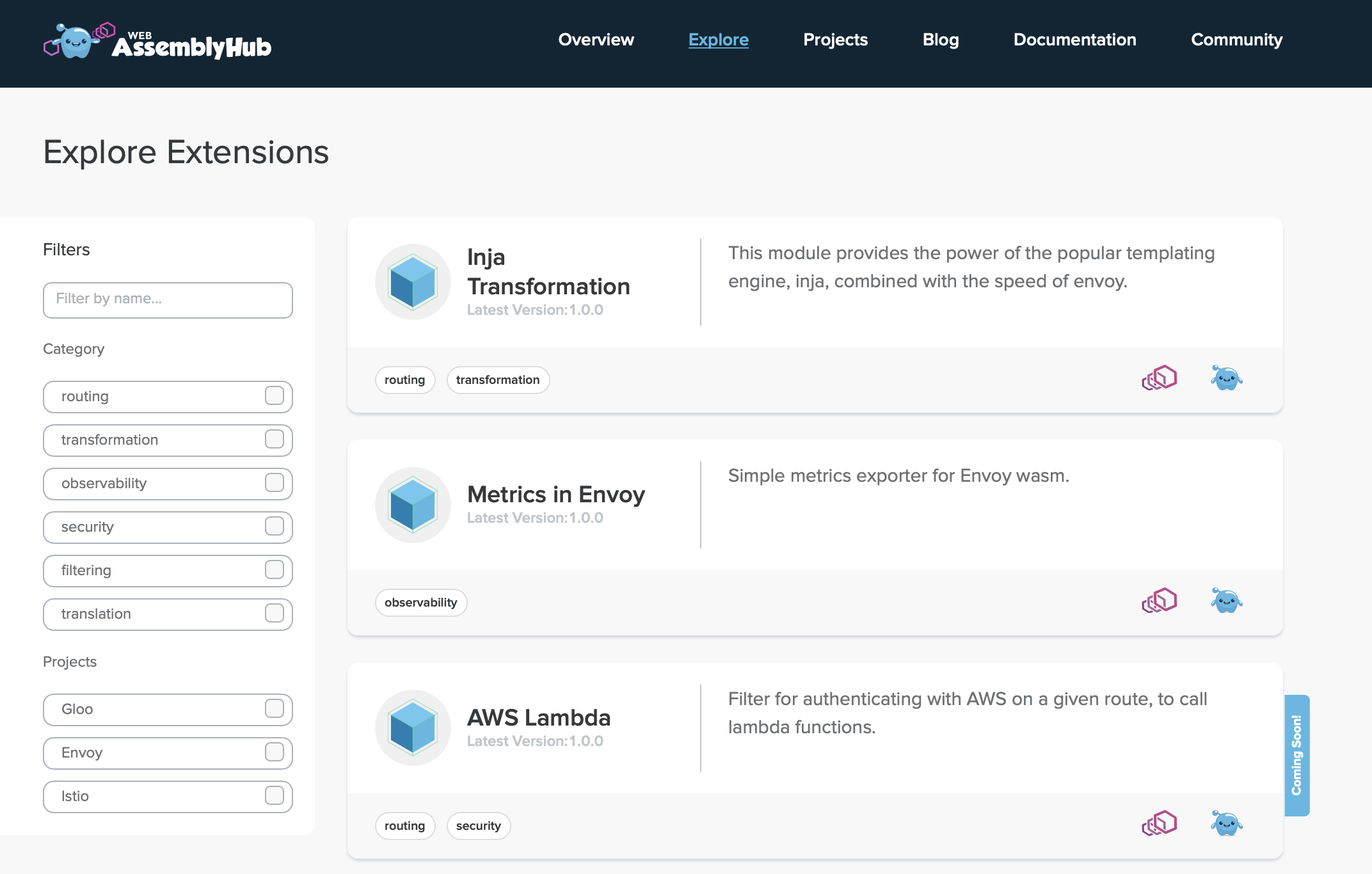

Solo.io has created a WebAssembly Hub registry designed to make it easier to discover and share extensions to the open source Envoy proxy server.

Now being developed under the auspices of the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) after being created by Lyft, Envoy is gaining traction as a proxy server in IT environments that have embraced microservices.

Solo.io CEO Idit Levine said DevOps teams are challenged by finding a way to extend the Envoy platform, which was developed using the C++ programming language. WebAssembly Hub provides an alternative approach to extending Envoy by employing the portable WebAssembly (Wasm) binary instruction format, known as a Wasm stack machine, that can be embedded as an execution environment in other platforms.

Wasm, which itself was developed under the auspices of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), provides a portable target for compilation of high-level languages such as C, C++ and Rust for building applications in a way that enables DevOps teams to add or modify extensions dynamically by moving code into a running Envoy process without having to stop a process or recompile code, said Levine.

That approach provides the added benefit of isolating extensions from Envoy, which means if the extension crashes it will not take down Envoy with it, added Levine.

Levine said Solo.io already employs Wasm to facilitate the development of extensions to Solo Gloo, an open source API gateway optimized for Kubernetes environments built on top of Envoy. Solo Gloo already supports the WebAssembly Hub registry.

As it turns out, however, Envoy is also at the base of the Istio service mesh. Any platform that employs Envoy now can take advantage of WebAssembly Hub to build and distribute extensions, said Levine. Among other use cases, Solo.io envisions DevOps teams using WebAssembly Hub to discover a web application firewall that can be added to, for example, an Istio service mesh via a few clicks of a mouse—which could significantly advance the adoption of best DevSecOps processes.

It’s not clear whether IT organizations will replace legacy proxy servers with rival offerings such as Envoy that claim to be more optimized for microservices architectures. In many cases, developers are making decisions based on personal preferences, which results in organizations soon discovering they are supporting multiple proxy servers across a range of classes of applications. Whatever the path chosen, however, those same organizations also may soon discover that a raft of extensions that were built for an Envoy-based platform may usurp a whole range of security, network and application services that today are all invoked in isolation from one another. The one thing that is clear, however, is that most of those services will be invoked programmatically instead of relying on an administrator who has mastered all the nuances of a specific graphical user interface for a single-function platform.

It may take a while for a new generation of proxy servers to achieve critical mass. However, at this point, it’s no so much about whether they will as much as it is to what degree.