Imagine

Imagine that you are designing the 2016 Range Rover line of sport utility vehicles. Like all gas powered vehicles, each one needs an exhaust muffler. Range Rover likely has narrowed in on a preferred provider of mufflers. But imagine what would happen if the designers and factory line workers could pick from any one of 27 past versions of that muffler from their preferred provider for the new model year. Yup, choose any one — even if it is outdated, lower performance, does not meet current emission standards, or has a known defect. Order it, place it on the vehicle, then ship it.

We all realize this scenario would never happen. No one would select a known defective part for the product they are manufacturing. And who would knowingly choose the 10 year old version of a muffler without the latest advancements to support air quality? No organization would give a each of their designers and line workers free reign on procuring any one of 27 different mufflers for a single model year. Imagine the operational cost of testing the different mufflers. Imagine the maintenance cost of having different versions of the same part shipping. Worse yet, imagine the liability of shipping parts with known defects.

Land Rover is not taking this approach, but software development teams are.

27 Versions

My latest research report, the 2015 State of the Software Supply Chain, reveals that large software development organizations sourced an average of 27 different versions of open source components that they used in development last year. To be more specific, out of the top 100 open source components these companies downloaded from the internet in 2014, they averaged 27 versions of each component.

While auto manufacturers like Land Rover have preferred suppliers of vetted parts, the procurement of open source components is often more of a free-for-all. If an organization has 300 developers, they effectively have a procurement department of 300 for sourcing externally developed software components. If you have 4,000 developers, you have 4,000 performing procurement. Even as we all know only the latest version of a components is the most feature rich and of the highest quality and integrity.

Not all organizations allow free-for-all sourcing practices for components. Fifty-seven percent (57%) have open source policies in place as a method to guide developers toward higher quality parts with the fewest known defects or security vulnerabilities. Organizations like Google mandate the use of no more than two versions of a given open source component across their development teams.

Good Cost, Bad Cost

What does this mean for a software development organization — especially one focused on improving it’s DevOps practices? First the good news: developers are using open source components to speed time to release and improve innovation. Both good things.

The bad news: Organizations are building mountains of technical debt through poor software supply chain practices by sourcing an average of 27 versions of the same component, impacting quality, complexity, maintainability, supportability, etc. They are doing this across the top 100 components being downloaded in a single year which equates to managing over 2700 different versions (when an optimized practice would only require the 100 best).

Organizations are sourcing component “parts” for use in their applications that have up to 26 known better versions available (more features, fewer bugs, improved performance, etc.).

Organizations are downloading and using parts that are sometimes 9 years old, or even older (simple math: open source projects release 3 – 4 new versions of their components each year). They are electively using outdated parts.

Organizations are also downloading some versions with known, documented security vulnerabilities. They are electively using known vulnerable parts.

Net Innovation Through Improved Sourcing

While we often hear people tout a DevOps mantra of “even faster”, there is a consequence to pursuing speed at any cost: technical and security debt.

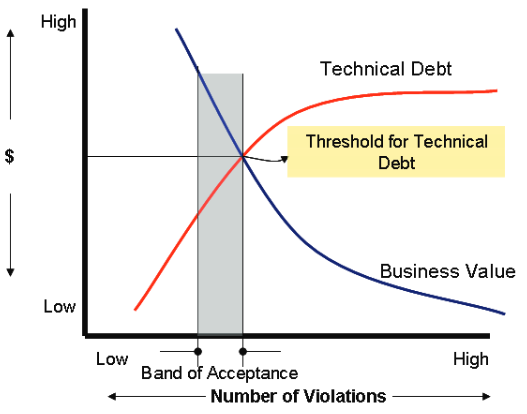

Open source components are enablers of speed. But free-for-all sourcing and use practices, add to technical and security debt that reduces “net innovation” and adds to the cost of operations. As technical debt grows, net innovation and business value drops.

If reducing the use 2,700 versions of 100 components was not motivating enough, consider this: the research also revealed that large development teams were consuming software components from over 7,600 external open source projects (suppliers). Including all versions of those components, they average organization consumed nearly 19,000 unique components in 2014.

Improved sourcing practices are just part of the overall story for improving net innovation and increasing business value. Improved sourcing practices can also enable more efficient operations, reduce mean times to remediation, and eliminate unplanned work for many DevOps practices. Improved sourcing practices have been employed across many industries resulting in sustained competitive advantages. Improved sourcing practices are part of a broader software supply chain management strategy.

Continuous Learning

There are so many lessons we can learn from other industries who have automated and optimized their supply chains — like Land Rover and other auto manufacturers. I’ll be sharing more of those lessons and perspectives from the 2015 State of the Software Supply Chain here this summer as well as expanding the discussion around “net innovation”. Stay tuned.